Ukrainian Church Reorganization & the Kaminskiy Letter

by Victor Czerkasij | 22 June 2022 |

In a recent Aunt Sevvy column Aunty quoted a General Conference leader saying that the Ukrainian Union was separated from the Euro-Asian Division (ESD) because of the inconveniences in travel and handling of funds, caused by Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. These current problems are undeniable, making the decision a practical one.

But there is more to the story. Adventism in Ukraine has a complicated relationship with what has been, through the years, Russian domination in the region.

The early years

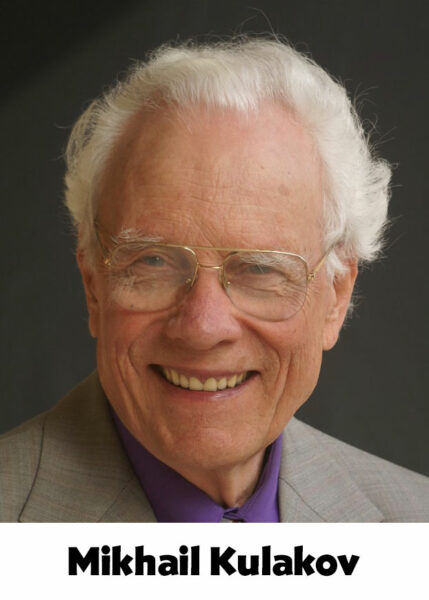

The early work in the former Soviet Union (USSR) was carried out under hardship and persecution. For spreading the gospel Mikhail Kulakov, a second-generation Russian Adventist, was arrested and sent to prisons and “corrective camps.” Though invited to attend international church meetings, Kulakov never received permission from Soviet authorities until 1970, when he secured a visa for a personal trip to visit a relative in the United States.

Kulakov met with then-General Conference (GC) president Robert Pierson at the GC building in Washington, D.C. This was a seminal event in Kulakov’s life. He returned to the Soviet Union determined to cement believers from the Central Asian and Baltic Republics, including Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova, into a cohesive church family.

Kulakov met with then-General Conference (GC) president Robert Pierson at the GC building in Washington, D.C. This was a seminal event in Kulakov’s life. He returned to the Soviet Union determined to cement believers from the Central Asian and Baltic Republics, including Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova, into a cohesive church family.

His work resulted in a historical Congress of Adventists in March of 1977. Kulakov was elected head of the Adventist Churches of the Russian Federation, and in turn secured government permission for the recently elected GC president Neal C. Wilson to visit the country in 1980.

The message from church leadership was for all Adventist factions and scattered groups in the region (which included Ukraine) to join with the organization that would eventually (1991) become the Euro-Asian Division (ESD). The Russian church also established the Zaoksky Theological Seminary in 1988, the first Protestant seminary in Russian history. It was built in Tula, Russia, and was opened to all Adventists eager for formal training as pastors and Bible workers.

The fatal flaw

But this organization was founded on a fatal flaw: it was centered in Moscow and rooted in Russian influence. These decisions hadn’t taken into consideration 500 years of Russian hegemony and authoritarianism in the region. And it would come at a cost, especially to the Adventist church in Ukraine.

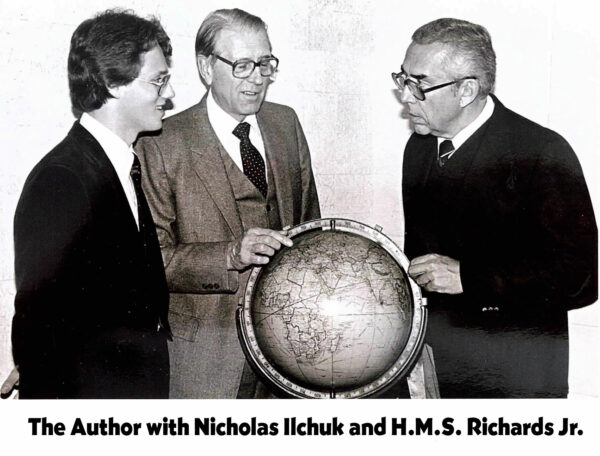

In his eagerness to further cement the church in that region under one roof, Neal Wilson in 1984 unilaterally closed the Ukrainian Voice of Hope (VOH). Located in Mountain View, California, the VOH was founded by Pastor Nicholas Ilchuk, a Canadian-born Ukrainian who had a burning desire to see the gospel taken to the Ukrainian people behind the Iron Curtain. Offices, recording studios, and printing presses for the translated Sabbath School Quarterlies, Signs of the Times and witnessing brochures that could be sent to Ukraine were at the Pacific Press Publishing campus and a bedroom in Ilchuk’s modest home. Sermons were created in cooperation with the English-language Voice of Prophecy, and H.M.S. Richards Jr. took great interest in the work of the VOH from his place at the newly built Adventist Media Center in Thousand Oaks, California.

In his eagerness to further cement the church in that region under one roof, Neal Wilson in 1984 unilaterally closed the Ukrainian Voice of Hope (VOH). Located in Mountain View, California, the VOH was founded by Pastor Nicholas Ilchuk, a Canadian-born Ukrainian who had a burning desire to see the gospel taken to the Ukrainian people behind the Iron Curtain. Offices, recording studios, and printing presses for the translated Sabbath School Quarterlies, Signs of the Times and witnessing brochures that could be sent to Ukraine were at the Pacific Press Publishing campus and a bedroom in Ilchuk’s modest home. Sermons were created in cooperation with the English-language Voice of Prophecy, and H.M.S. Richards Jr. took great interest in the work of the VOH from his place at the newly built Adventist Media Center in Thousand Oaks, California.

Wilson cut funding for both administrative support and salary for VOH. The message from the GC was clear: bring together the collective work of the church for this region in the Russian language alone. “Ukrainians understand Russian,” they said. “There is no need to provide the Ukrainian language.” As the VOH office closed, a new Russian Voice of Hope was established, headed by one of Kulakov’s sons.

Ilchuk never recovered from this blow. He continued to travel through Canada’s many Ukrainian communities using the Voice of Prophecy model, complete with a male quartet and rousing tent sermons. He saw the thaw in Soviet relations as an opportunity to reach out to Ukrainians who longed to hear the gospel in their own tongue.

But it was not to be. When the Pacific Press could not accommodate the ministry in its move to Idaho, Ilchuk retired in Oregon and died in 2002.

Relating to his work with Ukrainians, he penned these words in Ministry magazine in 1959:

Anything in their own language has a very special appeal to them and they will go out of their way to listen. …Our work for the foreign people will be more successful when we become thoroughly acquainted with their background, their history, their customs, their culture, and their religious faith and traditions.

Authoritarianism

In the forty years since the heady days of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness), the Russian penchant for authoritarianism has not diminished. Even in the early days of the Russian Republic, enthusiastic evangelism provoked government interference with religious practice and outreach. This became worse in 2016 when Russian president Vladimir Putin pushed through legislation that prohibited religious speech or evangelistic efforts outside of places of worship. Faith-sharing in any place other than a government-recognized church is prohibited. In those areas of Ukraine that Russia has taken over (Crimea, Luhansk, Donetsk and other cities in the far east and south), Russia rule has led to Protestantism suffering under heavy restrictions.

In Ukraine, both freedom of religion and the guarantee to worship and evangelize have been strongly protected. It is not unusual to see practitioners of the Falun Gong pass Hare Krishna devotees on the streets of Kyiv. And the Adventist church has been steadily growing in Ukraine, comprising a significant portion of the church in that part of the world. With freedom to travel and present the gospel, the bulk of the evangelistic activity in that region has been among Ukrainians in Ukraine, while the work in Russia has been in decline.

Ironically, the most effective resources for promotion and outreach to the public-at-large are the new studios of the Ukrainian Voice of Hope and Hope Channel, located at the headquarters of the Ukrainian Union in Kyiv.

In my discussions with Ukrainian pastors and leadership, they have quietly shared some of the more painful experiences of prejudice, both cultural and linguistic, while training in the Zaoksky Theological Seminary in Russia. At least partially in response to these concerns, in 2003 the Ukrainian church began training ministerial students in the new Ukrainian Adventist seminary, in the lovely suburb of Bucha, just northwest of Kyiv.

Tragically, Bucha became one of the early killing fields in the Russian invasion; Russian occupiers murdered over 1,000 civilians there. They also ransacked the seminary, causing great damage, though not destroying all the buildings.

The Kaminskiy letter

On April 7, 2022, the president of the Euro-Asian Division, Mikhail F. Kaminskiy, wrote an official document on church letterhead addressed to Adventist members in the Division. He requested that Adventists not watch or listen to prominent Russian-speaking pastors in America, naming Alexander Bolotnikov and Vitaliy Oleynik, because in their messages they pray for and support Ukraine.

Kaminskiy accused these pastors of an “attempt to change the commission of Jesus,” “sowing in the hearts of His children doubt and grief,” and described their ministries as “more destructive than strengthening.”

Kaminskiy accused these pastors of an “attempt to change the commission of Jesus,” “sowing in the hearts of His children doubt and grief,” and described their ministries as “more destructive than strengthening.”

Even more confusing are Kaminskiy’s words regarding the Hope Channel, an official media ministry of the Ukrainian Union. Referring to the Hope Channel’s attempts to provide Ukrainians spiritual comfort and direction during Russia’s brutal war on Ukraine and its civilians, Kaminsky accused it of “changing the character of its content and programs to an unrecognizable level.”

I have met Ukrainian pastors who are Pentecostal, Baptist, and Church of God who are very appreciative of the Ukrainian Hope Channel. But they are dismayed by the nationalistic comments of support by Christians in Russia for the war, including by Russian Adventists who have said publicly that churches should not be praying for Ukraine from the pulpit.

Kaminskiy has a right to his opinion. But in trying to limit whom members should listen to or pray for, he falls in line with the Kremlin propagandists who want to limit access to any information except what is state-approved. While Kaminskiy admittedly operates under unique pressure, his is far from the leadership displayed by Kulakov in the early days. His letter reflects the stain of tribalism, and resurrects ghosts of past conflicts where nationalism trumped community among believers.

Kaminskiy had the opportunity to show compassion to the suffering of fellow believers in Ukraine, all brothers and sisters in Christ. He did not. The timing of Kaminskiy’s letter, followed by the removal of the Ukrainian Union from the authority of Kaminskiy’s office less than a week later, suggests there was more to the decision than just practicality. Yet Kaminskiy remains in office.

While the GC Executive Committee voted 161-0 to remove Ukraine from the Euro-Asia Division, future consideration might be given to moving the ESD headquarters to Kyiv. Ukraine is a more stable, progressive, and openly democratic society, which would facilitate work in that region.

Freedom to preach

Before his passing in 2010, Mikhail Kulakov presciently said the following, which while speaking of Russia, also applies to the needs of Ukrainians:

Today I am greatly concerned about the underestimation of the importance of freedom of the individual. We have come through a very dark time when it is as if with an asphalt roller they tried to crush all individuality and to stifle the freedom of expression. It is impossible to forget that, and we should never forget it! These lessons should be remembered by those who care about the welfare of their native country, about their own children and the future generations. Each of us should think about the kind of foundations that we are laying today. So that the people of Russia could live a full life, filled with joy, with a sense of peace, and free from the fear that you will be silenced, oppressed and exterminated just because you desired to speak freely. This is crucial. This is what can save us as a nation and as a country from the horrors that we experienced in the twentieth century.

In 2016, Kulakov’s son Peter, a friend and well-known and appreciated pastor, arranged for me to preach at an Adventist youth rally in the port city of Odessa, Ukraine. I am a Ukrainian who speaks Ukrainian. But upon arrival I was nervously requested to speak English, and a Russian translator would be provided in the rented hall of a former Communist Youth building. I was disappointed, but gamely tried my best.

After ten minutes of my Friday evening sermon, I stopped and stood in silence. I then asked in Ukrainian, to the surprise of many, “Am I not Ukrainian?” The over 1,000 youth nodded their heads. “Are you not Ukrainian?” Many shouted “Amen!” I asked, “Am I not in Ukraine?” By now, applause. “Then please,” I requested the translator, “please let me speak my language to my brothers and sisters.” To the delight of the young people there and the many Ukrainian pastors who could only grin, the hall erupted.

By the next day, there was but one man who refused to meet with me or shake my hand—a Russian pastor who believed that I should only be speaking the Russian language. He angrily berated the Ukrainian pastors, who advised me quietly to continue speaking in Ukrainian.

One God, one heaven

Artur Stele said about the change in the Ukrainian Union’s structure that

We have the same Father. We are looking to the same heavenly Kingdom. Our people in ESD are members of the same family. They love each other, they care for each other, and wish the best for each other and plan to be together in heaven.

I say “amen” to that. But I also believe that we function best when we give regions permission to preach the gospel in the language and culture with which people are familiar.

Victor Czerkasij is an ordained minister who served as a chaplain at several academies and Director of Enrollment Services at Southern Adventist University. He has since become a dermatology nurse practitioner, and is completing his doctorate this summer. He resides in Cleveland, Tennessee, with his wife of 40 years.

Victor Czerkasij is an ordained minister who served as a chaplain at several academies and Director of Enrollment Services at Southern Adventist University. He has since become a dermatology nurse practitioner, and is completing his doctorate this summer. He resides in Cleveland, Tennessee, with his wife of 40 years.