Adventism in Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion

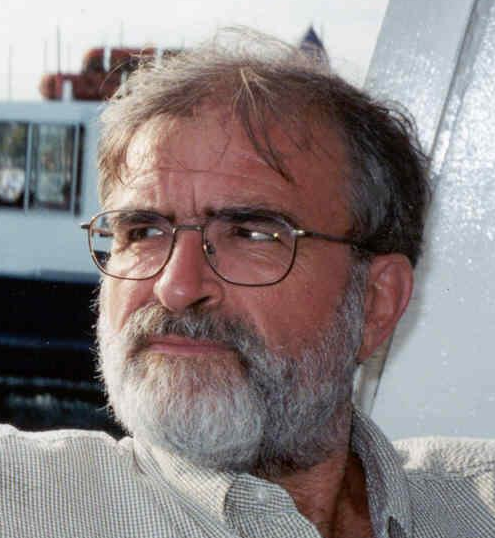

Ronald Lawson, Ph.D. | 24 December 2018 |

When the first edition of the Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion was being prepared in the mid-1990s, I was invited to write the article on Adventism for it. A decade later, Robert Wuthnow, its publisher, decided that it was time for a second edition, and I was invited to update my earlier article for that. The new edition was published by Congressional Quarterly Books in 2007.

We have just uploaded that paper to my web-site (www.RonaldLawson.net). I will introduce you to it here, and invite you to read the article itself.

Because the main market for this encyclopedia would be libraries, and especially university libraries, and most of those using it would therefore not be Adventists or likely to know anything about the Adventist Church, I began the article with a short description of Adventism and then sketched its origins and development. I mentioned Adventists’ urgent expectation of the Second Coming of Jesus, and the ridicule they received concerning their prophetic interpretations; also that their observance of Saturday as the Sabbath at a time when almost everyone worked on that day made it very difficult for them to find employment, while farmer members who chose to work their farms on Sundays after keeping Saturday holy faced arrest for contravening state “blue laws,” especially in the American South.

I brought that segment to a climax by explaining how Adventists saw an attempt to enact legislation making Sunday a holy day of rest in the 1880s as a sure sign that they were about to face persecution that would likely be interrupted by the return of Jesus. However, Ellen White had instructed Adventists to fight the legislation in order the “extend the time” for them to take their message to the whole world. This led Adventists to mobilize to defend themselves from the threat and to embrace religious liberty and the separation of church and state.

I see the Adventist decision to protect themselves through embracing religious liberty, and Ellen White’s leadership in placing this ahead of the fulfillment of the belief that the USA would pass a Sunday sacredness law, as growing out of the beginning of a development of less tension and more comfort between Adventists and governments, other churches, and society in general. Consequently, the Adventist journey through the twentieth century was marked by a series of accommodations with society. These were especially significant in times of war: World Wars 1 and 2, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. More recently, important signs of this process include the formation of ADRA in the 1980s and its drawing on vast government funds through such agencies as USAID, and in 2003 when Rear Admiral Barry Black, a former Adventist pastor who had become a naval chaplain and risen there to the top as Chief of Naval Chaplains, was elected as the 62nd Chaplain of the US Senate. Black was the first Adventist to hold that influential post; he was also the first not to come from a mainline denomination and the first African-American.

Another sign of Adventism’s growing comfort with the state and society was its appointment of a legal staff to pursue its interests through the court system in the USA. I spell out this trajectory by reviewing a number of important Supreme Court cases in the second half of the twentieth century. A significant symbol that illustrates the direction of the Adventist trajectory was the decision to trademark the name of the denomination, which occurred in 1981, and the manner in which this has been used in the courts in attempts to discipline several congregations and other groups connected to the church, such as SDA Kinship International.

Meanwhile, as Adventism globalized, this led to church-state relations in other countries, some of them with authoritarian governments. So I consider relationships between Adventists and Germany during World War I, with the Soviet Union under Stalin, Nazi Germany, and with regimes holding power in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, Adventists have also been elected to powerful positions in countries in the Developing World, such as Jamaica, Papua-New Guinea, and Uganda, where their presence had strengthened as a result of their missions. These development took the church leadership by surprise: because the influence of the church is so marginal in the Developed World, it had not been prepared to train Adventists concerning how being an Adventist could influence members in powerful and influential positions in such countries.

Ronald Lawson is a lifelong Seventh-day Adventist, and a sociologist studying urban conflicts and sectarian religions. He is retired from Queens College, CUNY, and now lives and works in Asheville, NC.

Ronald Lawson is a lifelong Seventh-day Adventist, and a sociologist studying urban conflicts and sectarian religions. He is retired from Queens College, CUNY, and now lives and works in Asheville, NC.