White Woman in a Black Town: The Jennie Ireland Story

By Jim Wibberding | 14 May 2021 |

Jennie[1] sank into a window seat, placed the leather satchel at her feet, and smoothed her blue cotton dress. As the railcar lurched and screeched into motion, she squinted out at the early twentieth-century bustle.

Jennie Ireland had poured ten years into this place, giving free healthcare to former slave families who came west to build their future. A gallery of tender memories hung in her mind but she had yet to paint specific scenes. Jennie liked teaching home remedies and good nutrition but . . . an unpainted image played in her imagination.

As the rhythms of the rail found their meter, she slipped her stout hand into the satchel and drew a worn pamphlet onto her lap, glancing from the title to the tent-strewn landscape ahead. A billow of steam whistled from the engine and the train slowed. Jennie had watched Furlong Tract take shape by the day, and her vision grew with every new house that stood where a tent once fluttered.

James Furlong had sliced up this tract of land in south Los Angeles and sold parcels to Black citizens, who pounced on the opportunity. Their aspirational spirit matched her own. Her finger touched the pamphlet title, as she glanced from it to the frame of a house in the making. It read, Our Duty to the Colored People—written by Ellen White. At age thirty-five, Jennie was ready to paint the memories that would color the next fifty years of her life.

Jennie L. Ireland is a forgotten pioneer, who crossed race and gender lines to shape the church we know today. Her name appears in lone paragraphs scattered through other people’s biographies, but it is time we tell her story.

Her daddy died when she was five, and her family found comfort in the hope their new Adventist faith promised. A small spark began to glow in the darkness when she saw that smile on her momma’s grief-worn face at her baptism.

That spark grew to a small flame, fed by pages of the Youth’s Instructor—a paper that crackled with stories of mission. The fire grew when her mom, Louise, moved her from Pacheco to Healdsburg to study at Healdsburg Academy—a mission training school. The flames spread when she joined the missionary ranks at age fifteen with a job at Pacific Press.

Jennie carried the torch to Battle Creek College for the nursing course (class of 1894), back to Pacific Press, and then to the Black neighborhoods of Los Angeles in 1896—where she now sat on a rocking train in a cotton dress ready to feed those flames with the words of a paper called Our Duty to the Colored People. It was 1906.

Jennie stepped off the train and made her way to her third floor office at the Southern California Conference. Her leadership skills had won her extra duties but no extra pay, and no one offered ministry credentials. She checked her hair bun with one hand and unlocked the door, then paused before entering. If she was going to do this, it would be on her own time and her own dime.

Later that night, in a prayer meeting at the Central Church, Jennie shared her dream—a quiver of nervous hope in her voice. “I believe God is leading me to start a church in Furlong Tract,” she said. “I don’t know how to begin. Please pray for guidance.” Jennie was being modest. Miss Ireland spent her days lost in thought and had a clear plan worked out. She just needed a meeting place.

As the ticking of the rails marked the minutes to home, Jennie eyed the sprawling lights of Furlong. They shone from windows in the homes of its ambitious Black residents, working to make a life in a world apparently not made for them.

In some small way, Jennie understood. She had been an orphan, was a woman with leadership skills in a world made for men, and remained a “spinster” in a time when many folks counted a woman’s value by the husband she won. Jennie knew life on the margin.

The next day, Sarah Cain, from prayer meeting, called. Her voice bubbled as she explained that getting her mail reminded her that the postman lived in Furlong. Jennie hung the phone on the wall and grabbed a coat. Eagerly, Miss Ireland and Miss Cain roamed the streets until they intercepted the unsuspecting postman—a Black man named Theodore Troy. Introducing herself, Jennie asked if he might host Bible studies in his home. Caught off guard, Postman Troy sputtered, “Uh, yes, my wife will be glad to have them.”

That was all the opening Jennie Ireland needed. By 1907, she had a big enough group to build a church. By 1908, the Southern California Conference made it official: the first Black Adventist church west of the Mississippi had burst on the scene.

That was all the opening Jennie Ireland needed. By 1907, she had a big enough group to build a church. By 1908, the Southern California Conference made it official: the first Black Adventist church west of the Mississippi had burst on the scene.

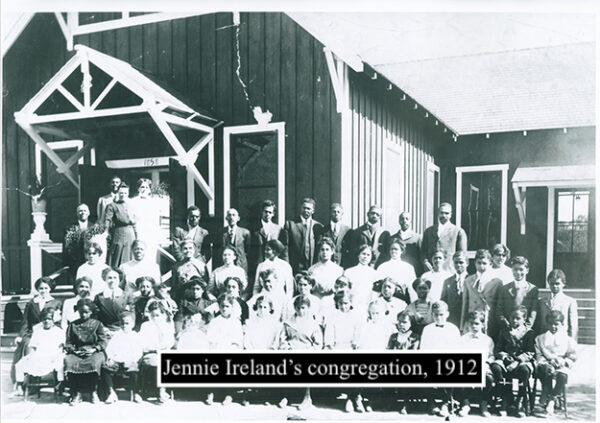

Jennie and her Furlong friends were just getting started. She pastored the church for eight years, growing it to ninety-nine members before moving on to plant another church in Watts, alongside two other women from Furlong. To join the Furlong church, Jennie insisted that you had to join the mission. With this in mind, they named it Furlong Mission Church of Seventh-day Adventists.

Jennie’s empowering approach resonated with her ambitious, free-thinking Furlong friends. They had designed their community governance to keep power in the hands of the people and help each other thrive. That mindset quickly jived with this woman bent to empower.

Jennie dreamed up her own ways of promoting Bible studies, evangelistic meetings, health classes, and more. Then, she taught every member of her church how to do the same—all of it. The cadre of leaders she trained went on to plant all the Black Adventist churches in Los Angeles in their time. As if that were not enough, several went beyond L. A. to shape Adventism and the world.

Jennie inspired fourteen-year-old Ruth Temple with stories of female doctors at Battle Creek, and told her she could do it too. She went on to be the first Black woman licensed to practice medicine in California, and a pioneer in public health.

Seven-year-old Owen Troy—the postman’s son—was enthralled with Miss Ireland and resolved to follow in her footsteps. When he came of age, he took Theology at Pacific Union College (PUC), then went back to learn more from Jennie. He became a key leader in Black Adventism and was the first Adventist to earn a doctorate in Theology.

Arna Bontemps was only four when Jennie started at Furlong but he caught the spirit soon enough. During his studies at PUC, he found his passion for literature. He grew into an architect of the Harlem Renaissance, which stirred optimism across Black America, and was one of the most prolific Black authors of his time.

There were others—lots of them. A half century of training leaders shaped Adventism and its neighbors in too many ways to count.

More slowly now, Jennie sank into a window seat, placed the worn leather satchel at her feet, and smoothed her black polka-dots. As the railcar lurched and screeched into motion, she squinted out at the mid-twentieth century bustle. Oxcarts had given way to Chevys, asphalt had replaced dusty streets, and fears had deeded the day to friendships.

In her gallery of memories, vivid scenes of new church buildings, evangelistic creations, and people now hung—most of all, people. These people now carried the torch—that same torch sparked in the heart of a five-year-old girl watching baptismal water drip from her mother’s smile.

On May 19th, 1961, Jennie L. Ireland slipped away.[2] She had spent seventy-five years in ministry, quietly shaping Adventism for generations unborn. Her method? Training leaders—the simple, persistent practice of pouring herself into others—others whom some saw as “other” but she saw as friends.

Race barriers couldn’t stop her. Gender bias didn’t slow her. Jennie’s story shows us what can happen when we escape the echo chambers of race and gender and, simply, give each other our best.

- Jennie L. Ireland’s story is constructed from extensive research in primary documents. These documents were provided by Office of Archives, Research, and Statistics at General Conference of SDA (documents.adventistarchives.org), Heritage Research Center at Loma Linda University (library.llu.edu/heritage-research-center), Center for Adventist Research at Andrews University (centerforadventistresearch.org), White Estate Archives (ellenwhite.org), Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research at University of California Riverside (cdnc.ucr.edu), and Family Search (familysearch.org). ↑

- “In Remembrance: Ireland, Jennie L.” Review and Herald 138, no. 31 (August 3, 1961): 25. ↑

James Wibberding, D.Min., is Professor of Applied Theology and Biblical Studies at Pacific Union College in California.

James Wibberding, D.Min., is Professor of Applied Theology and Biblical Studies at Pacific Union College in California.