What’s In a Name?

By S M Chen, posted Dec 8, 2016 by D Kovacs

“A rose by other name would smell as sweet.” –William Shakespeare, ‘Romeo & Juliet,’ Act II, Scene II

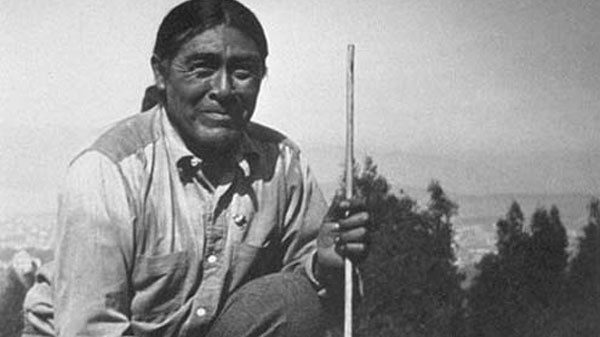

Not long ago I viewed a documentary on Ishi, one of the last of the Yahi group of the Yana, Native Americans indigenous to Northern California. At the age of 50, after four years alone (his tribe having been decimated) and near starvation, Ishi walked out of the foothills of Mt. Lassen near Oroville, in 1911. Anthropologists took keen interest in him, and for five years, he lived at the University of California Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco before – his body having little resistance to disease – succumbing to tuberculosis.

‘Ishi’ means ‘man’ in the Yana language. One commentator speculated that Ishi purposely did not reveal his true name in order to maintain his individuality and dignity.

Before passing, Ishi asked that, according to Yahi tradition, his body be preserved intact and not autopsied. That wish was not honored. Instead, his brain (like that of Einstein, with whom he perhaps shared more than we know) was sent in a deerskin-wrapped Pueblo Indian pottery jar to the Smithsonian Institute in 1917. The rest of his body, along with some Indian artifacts, was cremated.

In 2000, pursuant to a government edict, the closest surviving descendants of the Yahi tribe reunited Ishi’s cremains and brain, and he was given a proper burial in his homeland near Deer Creek Canyon in Northern California. One Native American commentator remarked that, at the time of interment, an intense bolt of light akin to lightning flashed from earth to sky, as if marking the return of his soul to its Maker.

*

We are often defined by our names. Baby name books, in addition to listing numerous names for the less than fully imaginative (I count myself among them), provide the meaning of those names. Just as well, for who would want our child to have a name with a pejorative, or less than wonderful, connotation?

Yet Isaac and Rebekah apparently had little difficulty naming Jacob. And, in his earlier years, he lived up to the meaning of his name. But, at a certain point, the deceiver became something else, and his descendants became known as the children of Israel, not of Jacob.

Other examples in Holy Writ include Abram becoming Abraham, Sarai Sarah, and Saul Paul.

This propensity for name change endures to the present, and seems particularly common in the entertainment and sports industries.

John Wayne was born Marion Morrison, and Woody Allen was Allen Konigsberg. Kareem Abdul Jabbar was once Lew Alcindor, Muhammad Ali was born Cassius Clay and Eminem used to be Marshall Mathers III. But (consistent with the concept of ‘less is more’; one name seems to carry more cachet) who recalls the original names of Bono, Cher, Madonna, Prince, and Sting?

Women, of course, often undergo name change when they marry. They may retain their middle name or their maiden surname, or both. However, in cases such as Elizabeth Taylor Hilton Wilding Todd Fisher Burton Warner Fortensky, the admiration for belief in marriage is perhaps superseded by a certain confusion. So much so that a public speaker prefaced his remarks by saying, “I feel a bit like Elizabeth Taylor’s latest husband. I think I know what to do, but am unsure I can make it interesting.”

In certain countries (e.g. Iceland), offspring’s surnames are often based on the father, so that a boy’s surname, if the father is named Johann, becomes Johannson, and his sister’s surname becomes Johannsdotter. This can be the cause of not a little confusion for those of us accustomed to members of one family all having the same surname. Telephone directories in such countries can provide a (perhaps insurmountable) challenge.

And, in other countries such as China, the surname appears first, given name last. While it may take a certain amount of getting used to, this name order seems based on logic that’s difficult to fault.

There is something reassuring about a literary work (“Moby Dick,” acknowledged masterpiece of Herman Melville) that begins: ‘Call me Ishmael.’

Or ‘My name is Asher Lev,’ novel by Chaim Potok.

Or ‘Confessions of Nat Turner,’ by William Styron.

There is nothing ambiguous about the name of narrator/protagonist.

*

The Godhead, it seems to me, lends itself to similar scrutiny.

While it remains mysterious, and may ever be so, the member of the triune Trinity who seems to have the most names is the Father. Variously called Yahweh, Jehovah, I AM, the Lord, and simply God in Judeo-Christian Holy Writ, He remains almost innominate, His name elusive. We’re unsure what to call Him. Perhaps that is one reason the disciples asked, “Teach us how to pray.” Names ascribed to Him seem more descriptive than definitive.

Were it not for the Incarnation, the name of the Son might have remained enshrouded. We know him as Jesus, Christ, the Savior. He was known as the Lamb, the Prince of Peace. He referred to Himself as the Son of man. But what was/is His real name (if He has one)? Like that of Ishi, we may never know.

The One who remains least nominate is the one about whom we also seem to know the least otherwise. He is called the Holy Spirit, or Holy Ghost. In fact, He may be no more spirit than the other two members of the Godhead.

But, upon further reflection, perhaps it matters not. We have been given enough information to digest. Further knowing might result in indigestion.

I am quite certain there are dimensions we do not, and cannot comprehend. Just as a two-dimensional creature confined to x and y-axes is not capable of understanding the concept of the verticality of the z-axis of three dimensions.

*

We ourselves are to have new names.

John says as much in the book of Revelation (Rev. 2:17; 3:12). The former verse speaks of a white stone containing a new name, perhaps like the thin printed-paper strip enmeshed in a Chinese fortune cookie, but, unlike the other, not for entertainment purpose.

I’ve read that some who believe in such matters have played the numbers printed on some Chinese fortunes and actually won a lottery.

But for those fortunate enough to receive the white stone it won’t matter. They will have already won the lottery which, in this instance, isn’t based on chance, and is of infinitely greater value.

S M Chen lives and writes in California.

S M Chen lives and writes in California.