The Sacred Cows of the Hebrew Faith, and How Paul Sets Them Aside

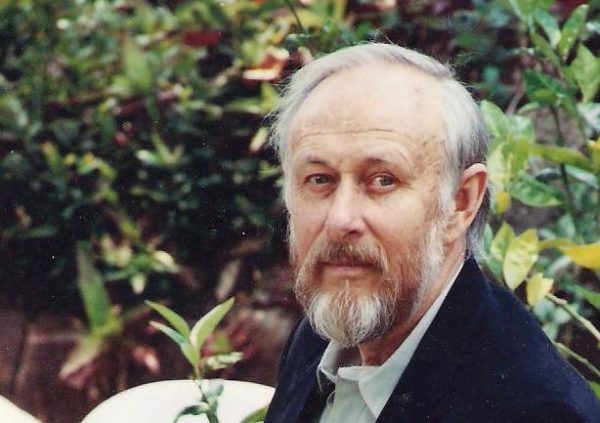

by Milton Hook | 4 June 2024 |

Paul’s letter to the Romans is one of his most iconoclastic. Writing after many years of being immersed in rabbinic law, in Romans he appears to turn his back on the sacred cows of the culture he once proudly owned and defended.

Here are the seven sacred cows of the Hebrew faith, and how Paul dismantles them in the book of Romans.

Circumcision

There was a haughty tone to the Hebrew declaration that they were “of the circumcision.” Those who were not in that category were lesser mortals, considered socially defiled.

Paul slaughters this sacred cow by noting that Abraham circumcised himself (ouch!) when he was ninety-nine years old and introduced the custom for all his male descendants (Gen.17:1-14).

But Paul quickly reminded his readers that prior to this time Abraham was assured by God that his descendants would be as numerous as the stars of the night sky.

Abraham believed this promise, and for that he was counted as a righteous man (Gen.15:5,6). That is, Abraham was considered to be a righteous man before he was circumcised (Rom.4:9-12). It follows then, according to this line of argument, that circumcision is unnecessary for salvation.

There can be no stronger argument than one cut from the Hebrew scripture itself. Genuine circumcision, Paul concluded, is a spiritual circumcision, a removal of guilt and the adoption of a life of faith (Rom.2:28,29).

Chosen and elite

Parallel to the hubris of circumcision was a conceit fostered by the Hebrew belief that they were the apple of God’s eye. They told themselves that they were in lockstep with God’s commandments, and that God spoke to them through their spiritually gifted prophets. They maintained that their bloodline, extending back to through their ancestors Abraham and Isaac, guaranteed God’s unconditional favour.

Paul destroyed this sacred cow, too. He insisted that salvation had nothing to do with ancestry. Instead, salvation is grounded in faith, for both Jews and Gentiles. God has no favourite race (Rom.2:10,11).

Paul’s conclusion was clear: everyone is a sinner, but anyone can be justified if they place their faith in Jesus, because the grace of God has no national or ethnic boundary lines (Rom.3:21-24).

Priests

The Aaronic priesthood was an essential element of Hebrew ritual. There was always the need for a human intermediary: the hoi polloi had to present themselves with their sacrifice to an ordained priest in order to facilitate forgiveness of sin and reconciliation with God. This was true even before the establishment of the Aaronic priesthood, when a tribal patriarch took the priestly role.

Paul demolished this fundamental sacred cow. He proposed that the priesthood is superfluous in view of the fact that reconciliation with God is now an existential experience, a spiritual reality made possible through a personal faith in Jesus (Rom. 5:11; 8:27).

Sin offerings

The daily and annual sin offerings made in the precincts of the Hebrew sanctuary were the foundation of the Jewish religious system. Every child of Abraham was expected to take part, especially during the various annual festivals.

Participation was a mark of Hebrew identity. The sacrifices were a tacit admission of personal sinfulness and the imperative to be reconciled to God by means of a sacrificial offering.

Paul killed this sacred cow, nullifying the need to offer any further sin offerings by proclaiming that the death of Jesus was a sin offering (Rom.8:3). Jesus did not die multiple times. Once was perfectly sufficient to bring about reconciliation with God.

The Mosaic code

The Hebrew code of ethics, said to originate from God on Mount Sinai and delivered by Moses, was paramount in Hebrew society. God’s demands on them were thought to be so stringent that each law became embellished with precise explanations, so that no one was left in doubt about how to observe the code in detail.

One’s salvation, it was thought, depended on meticulous adherence to the very letter of the law.

He begins in Romans 3 by asking this leading question, “What advantage is there in being a Jew?” He answers, “Much in every way!” This gives the impression he is about to provide an extensive list of advantages—but he offers only one: the Mosaic code that makes them a great nation and gives them the advantage over others.

By invoking the possibility of people unfaithful to the law, he likens their situation to a marriage: it is as if some of his readers were once married to the Mosaic code.

But the code died at Calvary, and those readers are now entitled to marry the risen Christ and “serve in the new way of the Spirit” (Rom.7:1-6).

Paul’s critics thought his brain had snapped. They accused him of being antinomian, giving license to debauchery. Paul vehemently denied it. His letters speak for themselves, for they generally conclude with exhortations to adhere to specific ethics.

Note, however, that Paul does not quote directly from the Mosaic code for his authority. Instead, his code is instructed by the exemplary life and teachings of Jesus.

Sabbath

The observance of the seventh-day Sabbath from Friday evening to Saturday evening was a distinctive part of the Hebrew faith—a very conspicuous sacred cow.

Interestingly, Paul never mounts an argument to urge its observance on his Gentile converts. “Some consider one day more sacred than another,” he wrote, “and others consider every day alike” (Rom.14:5). He left the matter open-ended, advising everyone to follow their own conscience.

Whatever you do, he added, do not judge a fellow-Christian to be an apostate if a difference of opinion arises over the question (Rom.14:10).

Paul appeared happy for this sacred cow to die a natural death.

Food taboos

Adherence to certain food taboos was another conspicuous sacred cow in Hebrew culture, principally outlined in Deuteronomy 14:3-21.

Once again, Paul is broad-minded on this matter. No food is intrinsically unclean, he categorically maintains (Rom.14:14,20).

While there are some Christians who eat all types of food, he observes that there are others who are strict vegetarians (Greek lachana—literally, eaters of greens or herbs). Even though he regards these vegetarians as weak, immature Christians he defends them, happy for everyone to follow their conscience.

His caveat was this: Don’t flaunt your eating habits in front of those who differ. Instead, “make every effort to do what leads to peace” (Rom.14:19).

Paul concludes that the ethical system as lived and taught by Jesus provides a better culture: simple, all-inclusive, and tolerant.

Let us rejoice in the Christian ethics and live lives of faith in Jesus!

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978), as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new SDA Encyclopedia.

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978), as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new SDA Encyclopedia.