The Hopeful: An Ambitious but Shallow Portrayal of Adventist Origins

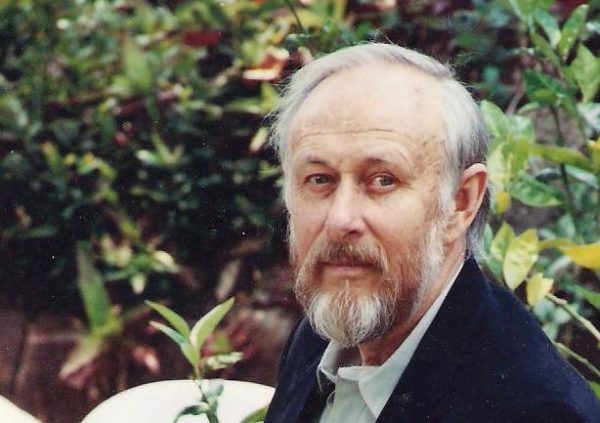

by Milton Hook | 29 October 2024 |

On October 22, 2024, one hundred and eighty years after The Great Disappointment in America, I watched the film The Hopeful in a movie theater in Australia.

There was only one other person in the three-hundred-seat cinema.

The intention of the director, Kyle Portbury, was to portray the origins of the Seventh-day Adventist denomination. The storyline begins and ends with John Andrews on board ship with his two children in 1874, as a Seventh-day Adventist missionary to Europe, telling a simplified version of the history of their church.

Indeed, the narrative level seems pitched for a twelve-year-old.

John Andrews’ story begins with William Miller, a soldier-turned-gentleman farmer, reluctantly turning to lay-preaching about the Second Coming. Miller adopts the year-day theory for his interpretations of biblical prophecy. He begins his countdown to an 1843 Second Coming by incorrectly proposing 457 BC as the start of the 2,300-day period of Daniel 8:14. The film offers only a passing reference to these foundational elements, making no critical analysis—because a twelve-year-old is not interested in Miller’s serpentine arguments.

Miller’s arguments

Let’s digress to outline Miller’s thought:

- The 2,300 days of Daniel 8:14 began in 457 BC and ended in 1843.

- The 70 weeks of Daniel 9:24,25 began in 457 BC and ended in 1843.

- According to Ussher’s chronology, Adam was created in 4025 BC. The period stretching to the time of Christ was 4,155 years. Add to that 1,840 years plus two more for Noah’s flood and three more for good measure, and one arrives at a total of 6,000 years ending in 1845. This heralds the Second Coming and the start of the seventh or Sabbath Millenium that begins in 1845.

- According to Revelation 9, the fifth trumpet began in AD 1299 and the sixth trumpet began in AD 1449, lasting for 391 years and ending in AD 1840.

- According to Daniel 7:25 the “time, times, and half a time” represents 1,260 days, beginning in 538 BC and ending in AD 1798. Add forty-five years for the Time of the End and one arrives at 1843.

- According to Leviticus 7, the “seven times” represents 7 x 12 = 84 months x 30 = 2,520 days. These began in 677 BC (claimed as the start of Israel’s captivity in Babylon) and ended in AD 1843.

- According to Daniel 12, the 1,290 days began in AD 508 and ended in 1798. Add forty-five years for the Time of the End, reaching to AD 1843. And 1,335 days began in AD 508, reaching AD 1843. Inexplicably, years for the Time of the End were not added to this latter period (Signs of the Times, August 15, 1840, 81; June 14, 1843, 115).

If the reader is not suffering a headache at this point, reflect for a moment about the insanity of nominating 1843 as the date of the Second Coming. (This was revised to 1844 and, soon after, specified as October 22, 1844). The year-day theory that led to the date-setting had been used multiple times by dilettantes who toyed with biblical prophecies. Their forecasts never eventuated.

What isn’t mentioned

The greatest weakness of The Hopeful is what it excludes. It is a sanitized version of our history. It does not give attention to the educated clergy of the day, men such as Daniel Campbell, Ethan Smith, and Baptist minister John Dowling—trained seminarians, and among the many ministers who publicly denounced Miller and his date-setting.

Most of the Millerite preachers, on the other hand, were frontier Methodists who proudly spurned theological training. They knew nothing about the nuances of the original biblical languages. They simply relied on the plain reading of scripture in the English King James Version of the Bible.

The Hopeful’s narrative then gravitates to the experience of Ellen Harmon, later White. She is depicted as sobbing in the garden when October 22, 1844, comes and goes without any sign of the Second Coming.

No mention is made of the vast majority of Millerites who soon abandoned the folly of date-setting. Miller himself continued to believe in the Second Coming, but shunned his complicated arguments that led to 1843 or 1844 or 1845. Leading Millerite preachers such as Sylvester Bliss, Josiah Litch, and Joshua Himes discarded their arguments. Likewise Apollos Hale, who started a shoe-shop to support his family, and Enoch Jacobs, who became American ambassador to Uruguay, both publicly admitted their error.

Tens of thousands of Christians never accepted Millerism, and those who did quickly deserted the ranks after the Great Disappointment. The Hopeful unfairly characterizes these clear-minded people as beer-guzzling boofheads. They are shown in sharp contrast to Ellen Harmon and a handful of close friends who persist with their date-setting and feverish expectations.

The new Adventists

A sense of elitism becomes evident. Ellen and her friends believe the door to heaven is shut for those who left Millerism. In a quirky manner The Hopeful accurately portrays Ellen’s thinking in this respect at the time, a view that her group comprised the saints and everyone else was forever lost.

The Hopeful shows Ellen (Harmon) and James White, together with Joseph Bates, as the legitimate inheritors of Millerism, an improved group of Adventists who added the Saturday Sabbath to their beliefs. (The film does not mention the Albany Conference, a meeting where the Saturday Sabbath was discussed and many adopted it.)

The narrative does portray the group’s increasing reliance on Ellen’s opinions. None of them were competent biblical exegetes; they relied on Ellen. She is depicted in the film as swooning on the floor, and then saying she heard messages in her head that sounded like an angel. No one else heard the messages—there is no objective corroboration for them. Like the year-day theory, the visions lacked validity. The Hopeful includes two characters, Sargent and Robbins, who reject her claims of receiving divine messages.

I walked from the cinema asking myself: What made the Millerites and subsequent Adventists hopeful? Apparently it was the belief that Jesus would return in 1844. And it was the belief that they would be saved because they “keep the commandments of God,” especially the Saturday Sabbath.

The Hopeful portrays them all as full of hope, not because of the hope of the resurrection or the gospel hope of justification by faith, but a hope grounded in the date 1844 and perfect obedience to God’s law.

To the contrary, the foundation of my own faith, my hope, is based on Christ’s resurrection. The resurrection did not get a mention in The Hopeful. I concluded it could have been titled The Delusional. I found myself thinking, What a weird mob! What a bizarre fringe of Christianity is illustrated in this film!

Back at home, I read some reviews of the production. One wrote, “rather empty and underwhelming.” There were kudos for the New England scenery and nineteenth-century costumes but others complained there was “no plot” and the message was “shallow.”

The message of the film was that failure grooms a person for success: specifically, the failure of the Millerites morphed into success for the Seventh-day Adventists. That message is intrinsically flawed because it can be demonstrated that failure more often leads to depression and despair, a sense of eternal loss and hopelessness.

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978), as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia.

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978), as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia.