The Evil Distraction of Time-of-the-End Timelines

by Loren Seibold | 1 May 2020 |

When I was about 12 years old I accompanied my mother one evening to midweek prayer meeting—a rarity in our congregation, since farm people don’t generally come out to evening meetings because of chores. But our pastor, Elder Schwab, was conscientious and determined to try. There were only six of us there, all women, and me. We each received a copy of a newly released book called Preparation for the Final Crisis, with Pacific Press book editor Fernando Chaij’s name on the cover. (I say only that his name was on the cover: not only was it mostly Ellen White quotes, but rumors persisted for years that Chaij actually received the manuscript from a Latin American pastor and adopted it as his own.)

I think it’s the only time I attended that midweek meeting series, because the way Jesus’ imminent return was presented—not as a blessed hope but an ordeal of suffering, betrayal, torture, and Divine abandonment—was discouraging. But even without my buy-in, Preparation for the Final Crisis has been a phenomenal success for Adventist publishing houses around the world. When my wife was a student at Glendale Academy, it was used as a textbook: students were expected to commit to memory the entire “schedule” of the end times. A friend at an Adventist press told me that it’s difficult to get exact figures on the number printed of a denominational book because any publishing house in another division can translate and print it, too, and Chaij’s name on the book made it a big seller in Latin American countries. That it is still listed as in print in catalogs of Adventist published writings after 50 years says something about Seventh-day Adventist spiritual appetites.

I respect Ellen White, though I think she’s been badly used. Rather than regarding her as a strong, courageous female church leader, the church has treated Ellen White as if she were virtually flawless, a mouthpiece for God. When I was young, we were taught to read Ellen White in a word-literal way with little regard for historical context or allowance for humanness, mistakes, personal opinions, editors, or borrowed passages. (Interestingly, we find it much easier to admit such things about the Bible than we do Ellen White!) As Elder A.G. Daniells warned at the 1919 Bible Conference, the failure to deal with those questions when they should have been addressed is bearing fruit in the current skepticism.

Some of what I object to about Ellen White’s writings was done not by her alone, but by those who took control of her reputation and writings after her death. The White Estate crafted a byzantine system to edit and control all she’d ever written, for over a century choosing to withhold significant portions of it even while telling us every word was necessary for our end-time instruction. Given their own testimony that she was nearly inerrant, it surprises me that these folks didn’t realize they were doing precisely what Adventists accuse the papacy of doing: holding ascendancy over inspired writings.

So it’s no wonder they were also responsible for the now-ubiquitous compilation, which tells loads about their, and our, hermeneutic of Ellen White.

The Worst Compilation Ever

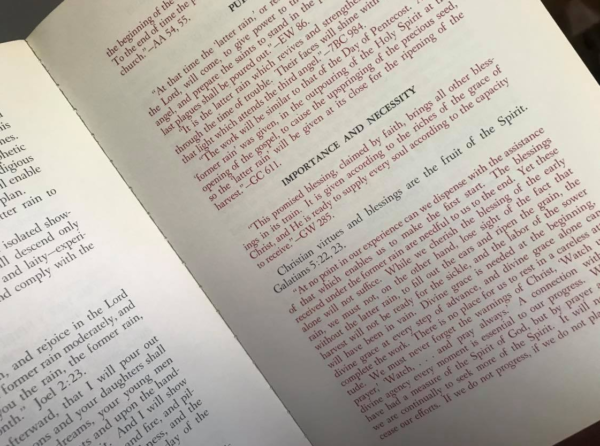

Preparation for the Final Crisis is a compilation, but one that eclipses the usual red-book compilation in nearly every way. The first thing that strikes you when you open the book is paragraph after paragraph printed in red ink. You’d think you’re looking at a red-letter Bible, until you realize that the red passages aren’t the words of Jesus, but the words of Ellen White! The Bible passages are in black, blending in with the ordinary text. Whether the editors understood it not, it’s hard to dodge the implication.

Not to worry, though, because there’s little enough Scripture here. Chaij says the Bible is only a general map of the future, but Mrs. White’s writings are “a precise itinerary.” This is a book devoted to a systematic scheduling of end time events from fractured, reassembled bits of Mrs. White’s writings. Chapter headings tell the story: “The Sealing”; “The Latter Rain”; “The Shaking”; “The Loud Cry”; “Persecution—The Confederated Powers”; “The Work of Deception: Spiritualism”; “The Early Time of Trouble”; “The Time of Trouble”; “The Plagues”; “The End of the Seventh Plague: Deliverance”.

Preparation for Jesus’ return, in Chaij’s scheme, amounts to knowing history before it happens. The Second Coming is God’s initiative, but it’s up to us to survive the mayhem by relying on the notes we took.

Preparation for the Final Crisis is a perfect example of what not to do with Ellen White. To take bits and pieces from the thousands of pages she wrote and assemble them into a topical pastiche changes everything. The context is gone. The narrative is gone. What may not have been meant to be specific becomes painfully so, and vice versa. The historical setting in which she wrote disappears. It is like killing live birds and stripping their skins to make a grand feather mosaic of a bird. It is certainly easier to study, but life, variety and richness are gone. The dynamic message becomes static and controlled. In Preparation for the Final Crisis, thousands of pages of writings are distilled into one intense, alarming volume which leaves the impression that our faith is about only one event in the whole history of salvation—as it happens, one Jesus warned us against speculating overmuch about.

We Don’t Need a Timeline

I defy you to find in the gospels anything that says we should be trying to put the time of the end on a calendar, or even a timeline. It simply isn’t there. The signs that we were warned about—earthquakes, wars, famines, signs in the heavenly bodies—are not klaxons of his return, but indications of business as usual. “You will hear of wars and rumors of wars,” is followed by “See that you are not troubled; for all these things must come to pass, but the end is not yet.” “For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. And there will be famines, pestilences, and earthquakes in various places,” is concluded with, “All these are the beginning of sorrows.” The darkened sun and moon and falling stars are explicitly stated as happening not until “Immediately after the tribulation” and immediately before “the sign of the Son of Man will appear in heaven”—not 200 years or more earlier. And directly to the point: “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, but My Father only… For if the master of the house had known what hour the thief would come, he would have watched and not allowed his house to be broken into. Therefore you also be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect.” (Matthew 24:6-8, 29-30, 36, 43-44)

That Jesus has waited 2,000 years since he said it, and another 200 since we were reminded of it, can only mean that he meant what he said: that we should be ready for his return at any moment, whether in a kaleidoscopic cloud explosion next week, or a thousand years from now, or you or me keeling over dead from a heart attack some time next month.

I ask again: what does “soon” mean? Next week? Next year? Within ten years? A hundred years? For how many centuries can people hear that it is all happening “soon” before the word becomes meaningless? Chaij quotes Paul in Romans 13:11 in defense of assembling this “precise itinerary.” Yet the text only says that we should be awake because “now is our salvation nearer than when we believed.” Obviously. But how much nearer? Who knows? Doesn’t Jesus say he will return precisely when we’re most likely to be off guard? So rather than cramming for Jesus’ anticipated return, this suggests a less dramatic, less stressful kind of faith: cultivating security of salvation and goodness of heart as a way of life.

This is a temptation that we Seventh-day Adventists have stumbled into time and again, if indeed, we ever really left it. From our first disappointments in the 1840s, we keep letting our eschatology slip back into being too specific for Scripture. A popular Adventist evangelist, Walter Veith, has recently recommended a date of 2027 for Jesus to return.

Naturally, we Seventh-day Adventists, knowing our history, would immediately object! We’ve heard about the Great Disappointment, and we’re not going to fall for that again, are we? On the contrary, several pastors have told me that their members are passing around this video, and have never been so excited!

And so it goes. We Adventists fall into the same trap again and again. If it’s not the GC president saying that Jesus will arrive before the next session, or that probation is about to close, it’s date-setting evangelists making money off of gullible Adventists. Someone is going to have to answer in the judgment for consistently ignoring Matthew 24!

(An aside: When Adventists place all their spiritual interest in what may or may not happen to the world in the prophetic future, they’re trying to avoid dealing with something that’s happening in their lives right now. I have seen this often enough as to suggest it is a rule.)

Yes, I want to be ready whenever Jesus returns. But to the point here, I can see absolutely no advantage in knowing the difference between the little loud cry and the loud cry, the time of Jacob’s trouble and the time of trouble (if indeed these distinctions have any Biblical merit at all). Neither can I see any value in blaming the Catholics for usurping God’s authority—especially when our own General Conference is going about saying that they’re the highest authority of God on earth! While religious liberty will always be an issue, why are we still talking about being persecuted for Sabbath keeping after 175 years of not the slightest sign of it?

Here, for what it’s worth, is the summation of my eschatology:

The only worthwhile preparation for the final crisis is being a thoughtful disciple of Jesus, the kind he described in his picture of the last judgment in Matthew 25 as one who would treat any needy person with sacrificial kindness. Anything you hear beyond that is an evil distraction that cannot but result in disappointment.

Loren Seibold is the Executive Editor of Adventist Today.

Loren Seibold is the Executive Editor of Adventist Today.