The Church That Taught Our Hearts to Fear

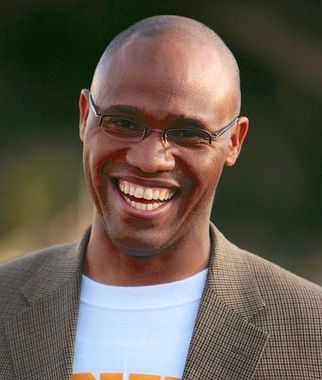

by Maury Jackson | 23 March 2023 |

This essay is reprinted from the Winter 2023 Adventist Today magazine, whose theme was “Belated Adventist Apologies.” On Sabbath, March 25, Dr. Jackson will be teaching the Adventist Today Sabbath Seminar on this topic.

I hold the greatest regard for my parents; they showed more courage and love than I could muster in several lifetimes. They met and married, then in the early 1960s converted from Baptist and Methodist Christianity to Adventist Christianity.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church awakened in my father a deep devotion to follow Christ. This devotion was strongly influenced by the writings of Ellen White. Following her counsel, my dad moved his family out of the city of Los Angeles. I was my parents’ first child born in the Mojave Desert. My five siblings and I attended Adventist Christian academies, ate a vegetarian diet, abstained from chocolate (because it contains trace amounts of caffeine), avoided listening to secular music on the radio, limited our television viewing to a couple of programs (It Is Written and The Waltons)—and God forbid that we’d ever get caught at the movie theater. For us, scrupulous rule-following went with the territory of the Adventist faith.

Nevertheless, some of my childhood memories leave me with unsettling and mixed emotions. I remember how one evening for family devotions, my father completed a long reading from Ellen White’s writings. What should have been a great opportunity to offer his children the assurance of God’s loving care proved everything but, because Dad’s reading ended with discussion on this passage:

“Those who are living upon the earth when the intercession of Christ shall cease in the sanctuary above, are to stand in the sight of a holy God without a mediator. Their robes must be spotless, their characters must be purified from sin by the blood of sprinkling. Through the grace of God and their own diligent effort, they must be conquerors in the battle with evil.”

And again, “In that fearful time, after the close of Jesus’ mediation, the saints were living in the sight of a holy God without an intercessor.” Wow, to stand in the sight of a holy God without a mediator—without Jesus at your side pleading for you!

I knew my siblings were not all as disciplined or scrupulous as I was. Some of them were even rebelling against it all. What if Jesus were to return before they got it together? I wondered. I negotiated with God that evening: If I would live a righteous life, then would he save my siblings and let me burn in hell in their place?

This attempted negotiation says as much about my early messiah complex as it does about morbid-minded religion. The teaching that our probation period with God will one day close before Christ’s return is heinous and inexcusable. If there is one thing God has to offer, it is time.

A Fearful Religion

Adventist Christianity creates a complicated history of religion and fear intertwined in strained and inextricable ways. The three angels in the fourteenth chapter of John’s Apocalypse sound warnings that have shaped a good part of its history: “Fear God and give him glory, for the hour of his judgment has come” (Rev. 14:7, NRSV).

The skeptic David Hume notes that “both fear and hope enter into religion; because both these passions, at different times, agitate the human mind, and each of them forms a species of divinity, suitable to itself.” It is inevitable in religion that fear is present, either to be expiated—that is, to be purged—or, in the case of morbid-minded religion, it takes up residence in the mind. In his book The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James says, “The worst kind of melancholy is that which takes the form of panic fear.”

Consider the various ways that Adventist Christianity has taken the natural, God-given gift of fear and perverted it to make it a tool of manipulation in the hands of ecclesiastical power:

- As described above, the repeated warnings of a time when we must stand before the presence of God without a mediator—a thoroughly frightening notion to those of us who can’t reach perfection

- Using Jesus’ imminent return, plus guilt about normal youthful urges, to drive sensitive-minded students to the altar during many academy weeks of prayer

- Artwork used by public evangelists, with ugly beasts and a menacing pope wearing a mitre, who was to shortly initiate a global persecution of Sabbath keepers

- The threat (originating with Ellen White) that even our parents and pastors would abandon us, leaving us to face persecuting authorities on our own.

- Repeated stories of Roman Catholics who would torture us, or about torture chambers in Catholic church basements

- Unending warnings about spiritualistic manifestations, including Satan personally revealing himself to the unwary

- The denomination’s denial, against the testimony of the New Testament, that there can be any security of salvation—teaching instead that individuals could go all through life doing their best for Jesus and trusting in him and his word, yet in the end be lost on a technicality

- Teaching that probation could close at any moment, leaving one bereft of salvation—and not even knowing it

Many youth raised in Adventist homes were introduced to these frightening messages early—and we are none the better, as Christians, for these rhetorical tropes. Fear crowded out healthy emotions, leaving us paralyzed and shrinking from a threatening emotional universe. Baptism in such a setting was less a sincere cleansing of conscience and more of an assault to make us teenagers cower in fear and submit to the preacher’s will in an effort to be saved.

Howard Thurman, the theologian who mentored Martin Luther King Jr., says that “this fear, which served originally as a safety device, a kind of protective mechanism for the weak, finally becomes death for the self. The power that saves turns executioner.”5 When it is sick, Christian religion turns the saving power of faith in the resurrected Christ into the slaying power of a death-producing paralysis. But healthy Christian faith returns the executioner named “fear” back to its rightful place among the motivating human emotions.

In other words, a healthy-minded religion knows that “faith is not propped up by hope of reward, nor by fear of punishment.”

Apologies Make Room for Reconciliation

Sometimes forgiveness comes without the ritual of an apology. My father and I have reconciled, now. I had forgiven my father, as he many times had forgiven me, before a word of apology was ever spoken. I have also grown to better understand his love through my own parental mistakes. Indeed, I never blamed him; he didn’t write those words, he only trusted those who wrote them.

Apologies, however, can be a step toward reconciliation, and I raise here the possibility that the church would do well to offer an apology for using fear to frighten people into cooperation.

Some of our mature members have, at least intellectually, overcome their fears and can now laugh at what used to frighten them. After all, “laughter makes the object of one’s fear small.” But others of us, once wounded, still carry scars. My childhood fears no longer control me, but neither are their effects gone, as evidenced by how well I can remember and describe them. Even if I have forgiven my church for manipulating me with fear, something was altered in my young psyche.

I would welcome an apology from the church for using fear to manipulate us young people, because some of those pastors, evangelists, and writers knew perfectly well what they were doing and employed fear because it worked so well to force their will on us.

Such tactics left many young Adventists with so many wounds and scars that they had to leave our fellowship, and it is unlikely that an apology will reconcile them to us again. Still, if an apology reconciles nothing other than the church to its true and best self, it has begun a great work. At best, it acknowledges and confesses a vision of God in Christ worthy of inviting disciples to, not propped up by hope of reward or fear of punishment.

Healing and Change

Reconciling Adventist Christianity to its best self means also drawing from our resources to heal the damage done to the sensitive. The Bible, like the revered Hindu Bhagavad Gita, “explores the psychology of the sensitive, caring human being at a loss as to what to do in a world whose ultimate origin and meaning remain the mystery of mysteries.” In the reality of this mystery, the one biblical command given more than any other is the command to “fear not”!

Sadly, the church seems unable to wean itself from manipulative fear. Graphic stories of persecution and insecurity are still told in our schools and Sabbath Schools. The evangelistic brochures still display images from the realm of horror. The era of fearful soul-winning isn’t over.

So, to be effective, the apology must be accompanied by change. Is the love of God not a sufficient motivator for our religious devotion? Perfect love casts out fear, says John (1 John 4:18). The kindness of God leads us to repentance, says Paul (Rom. 2:4, NRSV).

Yes, it is true that the gospel always delivers bad news before the good news. A clear statement of the problem must always precede a solution, so fearing the sin can be a first step toward receiving a healthy gospel. But although the bad news leaves us in a melancholy state (Christianity calls it “guilt”), a healthy-minded believer needn’t stay there.

The good news for those traumatized by fear is found in the doctrine of incarnation, by which I mean not quibbling over the metaphysical nature of a God-man, but learning from the gospel story how God in Christ models the relationship of the powerful to the powerless, the strong to the weak, the controllers to the controlled. God in Christ models and disorients the distorted power relationships that dwell at the root of fear.

Adventist Christians have resources to heal the fear-inducing results of denominational evangelists. With the message of God in Christ, the fog of fear will lift, for “whoever fears has not reached perfection in love. We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:18b-19, NRSV).

Maury D. Jackson chairs the Pastoral Studies Department of the H.M.S. Richards School of Religion at La Sierra University.

Maury D. Jackson chairs the Pastoral Studies Department of the H.M.S. Richards School of Religion at La Sierra University.