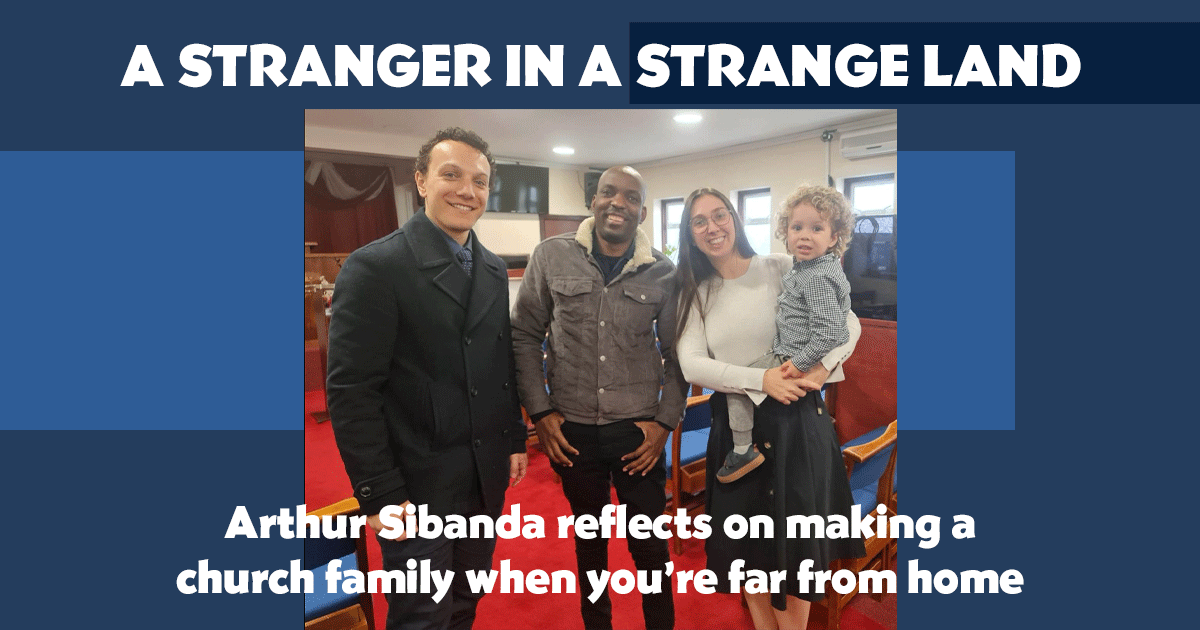

Stranger in a Strange Land

by Arthur Sibanda | 11 April 2023 |

And she bare Moses a son, and he called his name Gershom: for he said, I have been a stranger in a strange land. Exodus 2:22

Not long ago, I decided to leave the local congregation I’d been attending, and find a new church home. The one I’d selected was an hour away by train. There wasn’t anything wrong with my current congregation. They were welcoming and kind. The song service was vibrant and uplifting.

The only disappointment was that this experience was limited to the two to three hours of the church service each week.

Adjusting to a new culture

I have been struggling to adjust to a new way of life since I left Zimbabwe to work in the United Kingdom. This is a faster-paced life, more dependent on gadgets and technology. I marveled at how it was quite possible to spend a whole week indoors without going out of one’s home, thanks to online shopping and home delivery systems.

I hardly needed to speak to neighbors—indeed, I hardly saw them. Staying indoors with little human interaction can become depressing and lonely. Even when you can manage to take a walk on the streets or in the nearby park you will likely not speak to anyone as you walk about.

I had to learn how to conduct myself in public spaces. People in the streets of London appeared to be stoic, cold, and distant in demeanor. It was strange that I was not expected to greet strangers when I passed them on the streets. I would sit next to someone on the bus or train and not be expected to talk to them for the whole journey!

I do not mean to say the people in London are mean or rude; however, it is a culture with less public engagement than I’m used to. (Acquaintances have told me that people are more engaging as you move away from the huge metropolis of London towards the north—that while it could take years to earn an Englishman’s friendship, it would last a lifetime once it was established.)

Coming from what can be broadly described as communal culture in southern Africa, you would understand why these things puzzled me. But because I was keen not to offend anyone, I learned my lessons quickly.

The after-church depression

Every Sabbath after the church service I always felt a huge depressive emotional low as I walked out of church to catch the bus that would take me home. I felt like the worship hour on Sabbath was a “fix” that I needed, and walking from church to face the new week was like going through withdrawal. It was horrible! Any social connections I had made in church did not continue during the week.

Often I missed home. In Victoria Falls, I lived a stone’s throw away from church members. It was impossible to go through any day without meeting a member of my local church or a sister church. I had several church members who worked in the same place I did. It was common for me to randomly meet one of my church friends in the streets, and we’d have an unscheduled visit that filled my soul. (I would sometimes have to pick up a little “peace offering” to my wife for having made her wait while I drifted into dusk, unaware of passing time.)

In Africa, there always seemed to be extra time to accommodate an unscheduled appointment—unlike here, where we live with a sense of urgency, as though time is fleeting and every day must be hustle and bustle.

So I did not feel like I was fitting in well into my new church family. Of course, I missed my friends back home, and I missed my dear wife and daughter.

Healing with friendship

Yet it was Sabbath more than anything else that reminded me of what I lacked: a continuous social engagement that would continue during the week.

I opened up about my intentions to try another church to Sister Lynnette, a woman of Caribbean descent who had taken an interest in me and had begun to check up on me. Lynnette reminded me a little of my mother back home in Zimbabwe: she exuded motherly warmth and genuineness, which I felt every time she called. Lynnette urged me to stay and try to seek opportunities to be involved in church.

Another person whom I engaged was Lyndell (or as I sometimes call him, “Lindelwe”—an IsiNdebele/Zulu name meaning “the one whom we have been waiting for”). Our pastor had assigned him to be a prayer partner with me during one week of prayer, and I thought I might continue to be in touch with him after the prayer program was over. I spoke to Lyndell about my intentions to leave.

Unlike mother-figure Lynnette, he did not ask me to stay. Instead, Lyndell just listened. I always felt that he gave adequate attention to my musings and doubts. We became more acquainted as we had these conversations over the phone, but we hardly had enough time to speak on Sabbath, as he was busy attending to his church tasks, which were taking care of the PA system.

Then I had a crazy idea: what if I could deliberately turn this Englishman into my brother? But I feared how he and his wife would perceive my invasion of their personal space, given my perception of English culture as distant and unengaging.

I got up the courage to ask Lyndell if I could visit his home once a week. To my joy, he warmly accepted the request. The first weeks of this arrangement were hard for me. I was trying my best to do everything appropriately without ruining this chance for friendship. One of my fears was how easily I could fall into my “African time” default; I often found myself apologizing to his wife, Talita, for having overstayed the visit.

Talita graciously reassured me not to worry, as she was happy to host me each week. Lyndell always said I should not be silly and apologize when I was not doing anything wrong. I observed to myself that these busy Londoners seemed to be adjusting a bit to my “African time”—being more laid back and letting time roll while we enjoyed Christian fellowship.

Like I said, there seems to be more time in Africa than here.

Church family

I will not forget the day when Lyndell and Talita’s son Elias came with open arms to bid farewell as I was leaving. “Arthur, goodbye!,” he said with a big smile and huge hug. Young Elias had acted on impulse, and I felt that it reflected how he now considered me part of his family. (I must briefly mention that I also had to adjust to being called by my first name by people, including this precious little person.)

So while I do get to speak to Lyndell and his family rather briefly on Sabbath, there is another conversation I always look forward to on Monday or Tuesday evenings. The warmth of fellowship that I experience on Sabbath overflows into the week through the physical visit and the phone calls we have. When we meet, we talk about the week, family, and work, and we then have our prayer time, which Elias often joins.

I was delighted to introduce them to my family back in Zimbabwe over a video call, and I hope that this bond continues when my family eventually joins me here.

I have suggested to both Lyndell and Talita that we include more people in our circle, especially the young people in church. Lyndell already meets with some young men on Thursdays for football. We have made plans to share Sabbath lunches in the future.

This is the way of “doing church” I had been hoping and praying for. There is nothing that can compare to greeting little Elias on each Sabbath at church, and he says to me, “Arthur, will you be coming this week to my house?”

Let us not neglect our church meetings, as some people do, but encourage and warn each other, especially as now that the day of his coming back is drawing near. Hebrews 10:25

Arthur Sibanda is a mental health nurse from Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, now working in London, UK. He and his wife, Mercy, have one daughter, Nobukhosi Tashanta. He enjoys writing, composing songs, and singing, and is also involved in a ministry helping people overcome sexual brokenness.

Arthur Sibanda is a mental health nurse from Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, now working in London, UK. He and his wife, Mercy, have one daughter, Nobukhosi Tashanta. He enjoys writing, composing songs, and singing, and is also involved in a ministry helping people overcome sexual brokenness.