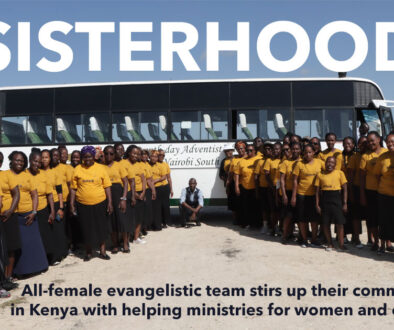

Remembrance of a Time Past

by S M Chen, posted 9-15-16 by D Kovacs I am an old woman now. The seasons have had their way with me. The spring has gone out of my step, I fall more often than I’d like. Summer has come and gone; I am in the winter of my years.

But, as I sit in a corner on a straw pallet, which softens the hardness of the underlying mud floor, and try to pursue some needlework which once posed little challenge, I am made aware just how much my vision has deteriorated and I put it down with a sigh and take up something that requires less visual acuity.

As I slowly and somewhat painfully rise to put a small log on a fire that has dwindled to embers, I let my mind wander and take me back to a time, many years ago, when my family, part of the ‘mixed multitude,’ departed Egypt.

I was but a girl of twelve then. My father was Egyptian, my mother not. My father told me of the time, when he was a boy, that he saw Moses kill with his bare hands an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew. Moses, hoping no one would know, hid the man’s body in the sand. My father wasn’t the only one to witness the crime. When Moses realized others knew, he feared for his life and fled the country.

My father grew up to be a taskmaster. It was a common job. But he was basically a kind man, and lording over Hebrew slaves was not to his liking. I don’t know how and why he did it for as long as he did. But then, I cannot fully understand what life was like for a man with a wife and children to provide for, the pressure he must have experienced. The lot of a woman’s life is not easy, and mine has been no exception. However, I don’t expect a man to comprehend my life any more than I can relate to his.

My father was particularly bothered when, years later, after Moses returned to Egypt, along with his older brother Aaron, the Hebrews were required to produce the same number of bricks after being told they would also have to procure their own straw. He wondered aloud about the cruelty of Pharaoh, but did so in muted tones, as his words could have been construed by some to be treasonous.

Those were some memorable times. Strange and wondrous things happened.

Aaron cast down his rod in front of Pharaoh. It became a serpent. Pharaoh’s magicians cast down their rods, which also became serpents. But Aaron’s rod devoured the other rods.

Pharaoh was unmoved. He refused to let the Hebrews go.

The waters of Egypt turned into blood. Fish died and stank. But the magicians were able to duplicate the metamorphosis. Pharaoh would not relent.

Frogs then appeared in great quantity. The Egyptian magicians were able to replicate this calamity. Pharaoh promised to let the Hebrews go if the frogs went away. The frogs died and were gathered in great heaps by the people. Their stench was worse than that of the fish – maybe because they were closer – and is almost as vivid today as I scratch memory. My nostrils yet twitch.

The next plague was lice. This the magicians were not able to duplicate, and they told Pharaoh, ‘The finger of God is in this.’ He ignored them.

Then came the flies. And the murrain that afflicted cattle, but only cattle of the Egyptians, not of the Hebrews.

Then the boils, which affected both man and beast in Egypt. The magicians were so uncomfortable they could not stand to be in Pharaoh’s court.

Then hail and rain, mixed with thunder and fire. Only the land of Goshen, wherein dwelt the Hebrews, was spared.

The locusts then came. In such quantity they darkened the sky. They ate every remaining green plant in Egypt. I remember asking father, “What are we going to do for food?”

The three days of darkness that followed, again sparing the land of Goshen, was almost a relief after the prior calamities. It gave one time to think, but it was apparently not enough time for Pharaoh, who told Moses not to come again, on pain of death. The tallow candles we had lasted only a few hours; for the remainder of the darkness we groped about like the blind, and I thereafter had a better appreciation of their affliction.

*

We heard about the last event which would precede the Exodus from some Egyptian family members of my mother. It sounded so far-fetched, my father disbelieved it.

Why would the firstborn of each household be slain? Had not the last few plagues spared the Hebrews? Might this next one be similar? Regardless, if the constellation of plagues had not convinced Pharaoh, why might he relent now? What if it were a false alarm? Wouldn’t we look foolish, along with countless others? Questions abounded.

My mother tried to reason with my father. She said, “What’s the harm of doing as the Lord has commanded the Hebrews?”

He was adamant that we should disregard such foolishness. No one was going to die that night. I wondered if he was as sure as he tried to make his voice sound.

She raised her voice, became argumentative, but not hysterical. Finally resorted to tears, which usually softened him. It didn’t.

*

It was the tenth day of the first month of the Hebrew calendar.

I looked over at my brother, sixteen, whom I idolized. He was in the bloom of youth. How could we risk losing him?

We were all aware how powerful the God of the Hebrews was. My father was just being stubborn. But my father and I had a special bond. Maybe, just maybe…

I went to him. He was sitting at the table, head in hand, contemplating. I stood beside him and caressed the lobe of his ear with my thumb and forefinger. He smiled.

“Would you let me try this?” I asked. “I know we’ll lose a lamb. But we might just save Joshua’s life.” I knew he might refuse me, but at least I will have tried.

Maybe he was tired of saying “No.” Or just tired.

In any event, he looked up and me, “Do what you must, child. I allow it.”

And he kissed my forehead. He did not look at my mother.

*

That is how it came about that I saved my older brother. And how, along with countless others, we joined the vast Hebrew throng that departed Egypt after centuries of bondage.

Although my hearing isn’t what it once was, I can still hear the wailing from that fateful night that arose on both sides of the land of Goshen. Like waters of the earth, it started small, then crescendoed into a mighty wave that engulfed us with the anguish of those who had lost. We held Joshua tightly and gave thanks.

The many miracles that were wrought during the 40 years of wandering in the wilderness – the parting of the Red Sea, the pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night, manna, the lack of sandal wear, water from a rock, quail, to name but a few – are they not described in detail by Moses, the Great Deliverer?

*

My parents are gone. Joshua is still alive, though older. He has his own family. And memories.

Another, younger Joshua, succeeded Moses as the leader of the Hebrews and led them into a land flowing with milk and honey.

I was young, and am now old, and have seen that the Lord of the Hebrews is not slack concerning His promises.

My name is Esther.

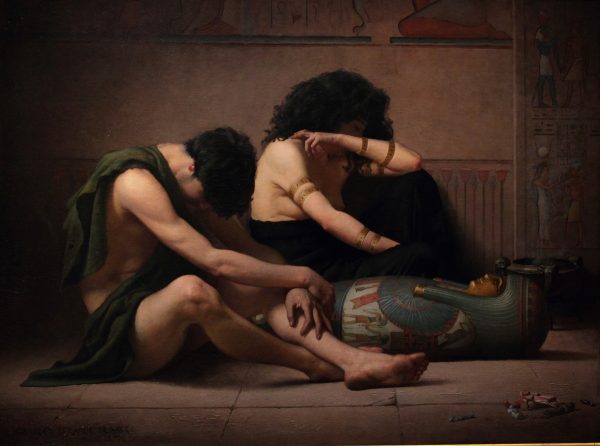

Photo credit: Lamentations over the death of first-born in Egypt by Charles Sprague Pearce (1877). Smithsonian Institute. In public domain.

S M Chen lives and writes in California.