Pascal’s Wager Revisited

by S.M. Chen | 15 November 2020 |

“Belief is a wise wager. Granted that faith cannot be proved, what harm will come to you if you gamble on its truth and it proves false? If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation, that He exists.” —Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

“Belief is a wise wager. Granted that faith cannot be proved, what harm will come to you if you gamble on its truth and it proves false? If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation, that He exists.” —Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

Blaise Pascal was a 17th-century French mathematician, physicist and philosopher. He contributed to all three fields despite a relatively short life—dead at 39.

His wager was the formulation, set out in his posthumously published Pensées, of a construct to deal with perhaps the most important question any of us face: is there a God (particularly as understood by Christians)? If so, should we choose to believe in such a Being and act accordingly?

Everyone must choose; not choosing is not optional.

Science cannot prove whether such a Being exists. But neither can it disprove such.

As American astronomer Carl Sagan commented, in a different context, “Absence of proof is not proof of absence.”

So here is Pascal’s Wager (one does not have to be a betting person or probability theorist to see the elegance of this matrix):

Examination of this construct shows that the bettor (which is every person ever born) only breaks even in the event that there is no god, as depicted in the lower/southern portion of the diagram.

In the event there is a God—a superior Being, however you understand Him/Her/It to be, Intelligent Design or equivalent—either the Northwest or Northeast quadrants apply. For the believer, there is the hope of an afterlife, a Good Place. It will be everlasting. For the unbeliever, another place awaits. For the sake of simplicity, its suffering is depicted as infinite. There is no second chance.

Even if a person maintains there to be a minuscule possibility/probability of there being a God, prudence may dictate choosing to believe (and act) as if such a God exists. This might be termed low-probability, high-stakes.

A believer might argue that the probability is not low, but agree that the stakes are indeed high.

In sum, a rational person should act as if God exists.

The Wager of Pascal has potential applicability elsewhere.

Take climate change. If climate change is real and we do nothing, planet Earth (the ‘pale, blue dot,’ as Carl Sagan called it, and the only place most of us will ever call home) faces catastrophic consequences. If we do something, we may mitigate those consequences.

If, as some maintain, climate change is a hoax, doing nothing will accomplish little. If we do something, there will be cost involved, but some resource outcomes gains.

The decision (as to whether to do something or not) may rest on the probability of climate change believed by those in power to act. As with religion/spirituality, there are scientists on both sides of the equation. However, the preponderance favors one side.

I have a 9-year-old grandson, my only grandchild.

I would much prefer that he look back at my generation, perhaps the last able to make a dent in climate change, with fondness at our perspicacity rather than wonder why, when the majority of experts agree on the reality of climate change, we insisted on maintaining our current lifestyle and did nothing.

If not for ourselves, for those who would follow.

I don’t know where the majority of spelunkers stand on this issue, but their credo resonates with me:

Take only pictures.

Kill only time.

Leave only footprints.

The wager has other application.

I recently encountered an essay that I found heartwarming.

I had run into Tractor Supply to get food for my chickens and my cats. I was lingering in the lobby by the front door, looking at amaryllis and daffodil bulbs, when a tall, slightly pungent man leaned over as if to see what I was looking at. When I straightened up, he made eye contact with me. He said, “I’m hungry, ma’am. Do you think you could buy me a few snacks?”

I had a fleeting moment when I thought, “Not now. I have to get to a meeting. I don’t want to get involved.” Then I looked into his pale, earnest eyes and said, “Sure.” It was my opportunity to practice generosity and compassion, to give from the abundance which I have been given. Of course, there was always a chance that I was being scammed, but when I looked at his tattered jacket and the holes in his boots, I was willing to take that chance.

We went into the store and he selected his snacks, first carefully and then with abandon. Beef jerky, nuts and candy all went in the pile. He asked me if I was a farmer. I said no, and he said he was raised on a farm. He said he had stood and read some of the farm magazines before I came in. Then he went off on a tangent about inventions of farm implements in a stream of consciousness that I found difficult to follow.

I excused myself to go and pick up the items I needed. When I returned, the pile on the counter was quite large. The clerk seemed a little flustered by all this, but she began ringing it up.

While she was ringing up his food, he had fished around and found a little wad of plastic which he carefully removed from his pocket. He unfolded it, and among the scraps of paper and other worthless treasures, he found two pennies. He asked her to put them against the total. She looked at me questioningly and when I nodded, she deducted the two cents from the total.

$55.00 later, he gathered his bags and without much fanfare, he left. He was mumbling to himself as he went through the door, then he turned around and lifted his hand and said, “Thank you, Ma’am.”

I looked back at the clerk and her eyes were bright with tears. “There are still special people in the world!” she exclaimed. I agreed with her, thinking she meant this humble soul who had asked a stranger for a favor, but wanted to feel that he had contributed his share. But then I realized she was talking about me. I thought she missed the point.

“It could be any of us,” I said. “Any one of us.”

There was a gentleman standing behind her in street clothes who told her he would stay — he had a gun. It slowly dawned on me that he felt the need to protect this store clerk from this poor homeless guy. He gave me a quizzical look and I said, “I believe we are on this planet to help one another.”

His eyebrows went up and he said, “You are exactly right, ma’am.”

When the clerk realized that she had put the receipt into the bag with the homeless man’s food, she was stricken. “Your receipt had your phone number on it!” she said. Then she hastened to add, “I’m sure he means no harm,” but it was obvious she was not so sure. I, on the other hand, felt sure this man didn’t even own a phone.

As I was leaving, she again commended my act of kindness and I looked straight at the man with the gun. I used language that I knew he, a product of the Bible Belt South, would understand. “You can’t out-give God,” I said, pointedly looking at his holstered gun. His face lit up and he enthusiastically agreed.

When I got outside, the homeless man was still in the parking lot, standing with his bags, talking to himself. He turned to me and smiled, starting, again, a stream of impossible-to-follow conversation. I offhandedly asked him for the receipt.

“Oh, do you want to tear your phone number off of it?” he asked.

“No, I just want the receipt.”

“You can use it for a tax deduction,” he instructed enthusiastically.

“I don’t need a tax deduction,” I said, laughing. “I just want it to remind me of you.”

He seemed taken aback by this, but he handed me the receipt. He thanked me again and then picked up his bags and strode on his long legs across the parking lot into the dark.

“Stay warm!” I called after him. Then I said a prayer for him and asked for his safety. As I drove away, I felt that I had had the opportunity to be face-to-face with the Divine. The Bible says that we have opportunities to entertain angels unaware. If that is true, and I don’t find that hard to believe, I think that this tall, humble, homeless man was sent to give me the opportunity to respond to human need with compassion and kindness and generosity. His presence was a test. And a gift.

I still have that receipt tucked into my journal to remind me of the chances we are given every day to reach out to others and meet them at their point of need. If we can put aside our fear, and see that we are all just doing the best we know how to do, we can be much more effective in bringing change to our world.

In the story, the author mentions the possibility that the man she helped might have been an angel in disguise. I agree with her. We are told that, by entertaining strangers, we may have encountered angels. The author might have rebuffed the stranger whom she ended up helping. Not helping is so easy and the default mode for many.

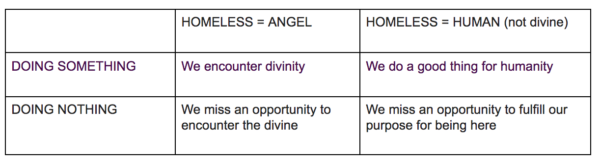

I have constructed a grid similar to the one previously depicted for Pascal’s Wager for our potential encounter with the divine. Here’s what it might look like:

While this variant of Pascal’s Wager might not have the ultimate ramification of the original Wager, I shudder when I contemplate how many times I chose to not help someone in need when I was in a position to do so. Whatever reason I had was not good enough.

If angels walk among men, they almost certainly won’t appear as some imagine them to look: beings of intense lightness/brightness, perhaps with wings. They are likely to appear as humans. If so, they probably will seem quite ordinary. Even potentially repulsive (to some). But they are no less God’s children than we. Perhaps more so (Holy Writ indicates angels were created to be above man; how much more so is unclear).

The Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, whose morality tales my father used to read me when I was a boy, became a Christian in later life. In 1885, he wrote a short story called “Where Love Is, God Is.” A poor cobbler named Martin, after reading the Gospels of Holy Writ, hears a voice telling him he will be visited by divinity the next day. Martin encounters and interacts with a number of people the next day. By day’s end he thinks he was stood up by God, only to be told that the various people he met were human stand-ins for the divine.

Unfortunately, one cannot turn back the hands of the clock or resift the sands of time.

Fortunately, so long as we breathe, there is an opportunity to do good, to become more enlightened, to be better.

That alone may be a cause for gratitude.

S.M. Chen writes from California.