My Political Evolution as an Adventist Christian

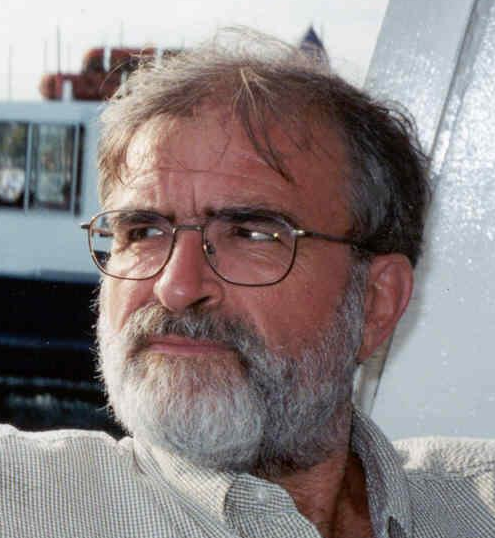

by Ronald Lawson | 19 September 2020 |

I grew up in a devout Adventist family in Australia. My father was a newspaper editor and manager of a printing works who, at the end of a difficult 16-week printers’ strike, during which he and the apprentices had had to produce everything, decided to do what he had always wanted to do: he became a farmer—a pineapple grower. He was elected to the board of an enormous new pineapple canning factory, and he got to know well the Country Party Premier of the state of Queensland.

The Country Party was Australia’s most conservative political party. I recall, at age 9, watching with fascination the 1949 federal election that installed Robert Menzies as Prime Minister, by means of a coalition of the Liberal Party and Country Party, the two conservative parties.

My parents were excited about the new government. I never remember them considering whether their faith should influence their vote. They voted what they perceived to be their own interests, which included economic policies and Menzies’ strong commitment to the British monarchy, and to strong economic ties with Britain.

This tendency to consider personal interests first was typical of Adventists and church leaders—which seemed strange considering the fabric of the rest of Adventist beliefs. The notable exception was when a United States presidential candidate was a Roman Catholic: Adventists there voted strongly against John F. Kennedy in 1960, fearing that he secretly planned to enact a Sunday law.

Personal decisions

My first personal decision with political ramifications, where I had to exercise some independence and think about matters of faith, occurred at the beginning of 1958. On my 18th birthday, I had to register for the draft in Australia. Even though the Korean War had ended and the Vietnam War was still in the future, conscription to military service was still active in Australia. I had to decide how to register.

The Adventist church in Australia urged us to register as noncombatants, so that we could both show our nationalism and avoid killing. However, my study of history had already alerted me to the horrors of war and how much evil was rooted in nationalism, and I ultimately chose to register as a conscientious objector. My conference youth leader was willing to vouch for me when I was called to a hearing, recognizing that my decision was rooted in conscience.

I was already becoming an internationalist, for I saw that God’s people were everywhere. Two months later I entered university in the Honours in History program. Four years of in-depth study of history strongly reinforced my conviction that nationalism was a false god.

Poverty and inequality

I went on to complete a Ph.D. in both sociology and history, preparing to become a historical sociologist. Sociology taught me to examine data seriously. I learned about the inequality in society, as measured by such things as socio-economic status, and how it shaped so much of life, such as opportunities for education, medical treatment, and housing. I also learned about how strongly those who were wealthy maneuvered to continue and increase their advantages.

I became increasingly aware of how strongly this contradicted the teachings of Jesus concerning refugees, strangers, and the poor.

While a graduate student in Australia I had become involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement, and had been influenced by the writings of Martin Luther King Jr. and the American Civil Rights movement. I began to see protest as one of the few ways where citizens from disadvantaged groups could attempt to right the wrongs that they faced in societies.

I came to Columbia University in New York City on a Fulbright grant in September of 1971. I remember that I regarded Professor Herbert Gans’ class on Human Poverty as data and understandings that Jesus would have me know.

I had arrived in New York City just after the state government had passed legislation that ended rent controls that had been in place since early in World War II. Many landlords immediately took every opportunity, legal and illegal, to evict tenants with low rents, in order to raise the rents substantially. I wrote a paper on two neighborhood tenant organizations that had emerged in an endeavor to keep tenants from being thrown on the streets, and this so impressed two professors that they invited me to submit a research proposal through their research shop to carry out a broad study of tenant activism over time as well as currently, and I was awarded a large grant which ensured that I would not go back to Australia any time soon.

I also became a faculty member at Hunter College in the City University of New York, where I taught courses on housing problems and protest movements. The latter led me to know movements such as the labor movement, the Civil Rights movement, and the feminist movement well.

Recognizing my homosexuality

Early in 1974, after 15 years of prayer and failed struggle to be heterosexual, I came out as a gay person, and that year, when I attended my first meeting of the American Sociological Association, I witnessed a horrendous example of discrimination and hatred that moved me to announce the initial meeting of the Sociologists’ Gay Caucus, where I should not have been surprised that I was elected president—a position I held for four years.

Meanwhile, wishing to find an Adventist partner, in 1976 I placed an ad in the national gay paper inviting gay men to write to me. I received between 40 and 50 replies, which unexpectedly contributed to the formation of SDA Kinship, a support group for LGBT Adventists. I warmly embraced all these causes, seeing this as the kind of thing Jesus would have me do.

A sociologist of Adventism

In 1984, having been promoted to full professor and received tenure, I felt safe in launching a long-planned sociological study of global Adventism. One of my foci was social issues within the church: the inequality of women, racial minorities, LGBT youth and members, the divorced and single, unmarried mothers, the sexually and physically bullied and abused, and Adventists with AIDS.

I also studied Adventists and politics, and was dismayed to discover that the Adventist Church regularly felt more comfortable relating to dictators, ranging from Hitler and Stalin to the military rulers in Latin America and South Korea, than democratic regimes. I interviewed dozens of Adventists who had climbed to positions of political influence and power in developing nations such as Jamaica, Uganda, and Papua-New Guinea, and discovered that when I asked them how their faith had influenced the policies they pursued they looked at me blankly: they had not even considered that possibility.

I was also dismayed to realize that most Adventists in democracies seemed to vote without considering either to what extent the policies advocated were attuned to the principles that Jesus had enunciated, or the characters of the candidates as demonstrated by the lives they had lived. Unless, of course, a Presidential candidate happened to be a Catholic!

American politics

I have now lived in the US for nearly 50 years, and I have dual Australian and American citizenship. I have been upset many times because almost every president has gotten us engaged in wars; by the willingness of presidents to lie to us—e.g., in order to gain support in invading Iraq; and by their reluctance to welcome the needy and strangers.

I was excited by Obama’s election, because of his intelligence, his wish to expand the coverage of medical insurance, and as a symbolic break in the widespread discrimination against blacks here—but I wish he had been less timid in choosing what policies to pursue. I realized that the way my understandings have developed, and the influence of my faith on this, has placed me somewhat to the left of the Democratic party. This did not seem so unusual in New York City, or in the Adventist Forum community there, which was my main reference group for the whole time I lived there—45 years.

Because of living in New York City, I hadn’t known a committed Republican well. However, after my move to Asheville, North Carolina, in 2015, I was amazed to find that a large majority of the white Adventists in that heavily Democratic city had voted for Donald Trump in spite of his lowlife remarks about women, his hatred of refugees, his rejection of young non-citizens who had lived in the US since they were very young, his readiness to dismantle programs protecting the environment and people with pre-existing medical conditions, and his fanning of the flames of racial conflict. Asheville is the headquarters of the Billy Graham organization, and I was hurt and astonished when many Evangelicals embraced Donald Trump. But why Seventh-day Adventists, whose prophetic beliefs should have made them cautious of such ideas?

I should make it clear that I have never been an activist for a particular political party, nor do I support any party financially. I am expressing my surprise that Adventists usually do not weigh the policies embraced by political candidates against the basic teaching of Jesus and the Bible.

It would be good to discuss the principles we as Adventist Christians should use as standards against which to evaluate candidates. I suggest that based on the principles of loving our neighbors as ourselves, treating all equally, and taking special care of strangers and the poor, these should include policies towards refugees and immigrants, that impact the status of women, racial minorities, and other groups that face discrimination, and that protect vulnerable people from exploitation and abuse.

As Adventists who believe that God cares about health, and who appoints us as stewards of creation as we remember the Sabbath, we should be concerned with the provision of health insurance to all who are vulnerable, responding with determination to diseases that threaten the health of the population and the economy, such as COVID-19, and with strengthening policies that protect the environment.

We should also be concerned to evaluate the lives of candidates in terms of honesty, truthfulness, stability, unselfishness, and how they treat others, especially those vulnerable to exploitation and mistreatment.

I am sure that you will be able to think of other important measuring rods for us to employ as we make our decisions concerning who most deserves our support as followers of Christ.

We are about to vote to decide between awarding Donald Trump another term versus exchanging him for Joe Biden. Will Adventists reject Biden, perhaps because he is a Catholic, and help re-elect Trump in spite of his stand against so many of the principles put forward for us by Jesus?

As for me and my house, we feel called to vote for a change.

Ronald Lawson was Professor in the Department of Urban Studies at Queens College, the City University of New York, where he taught courses focusing on the sociology of religion and political sociology. He is also the President of the Metro New York Adventist Forum, a position he held for 41 years. He is completing a book, Apocalypse Postponed, that will give a sociological account of international Adventism, the first major study of a global church.

Ronald Lawson was Professor in the Department of Urban Studies at Queens College, the City University of New York, where he taught courses focusing on the sociology of religion and political sociology. He is also the President of the Metro New York Adventist Forum, a position he held for 41 years. He is completing a book, Apocalypse Postponed, that will give a sociological account of international Adventism, the first major study of a global church.