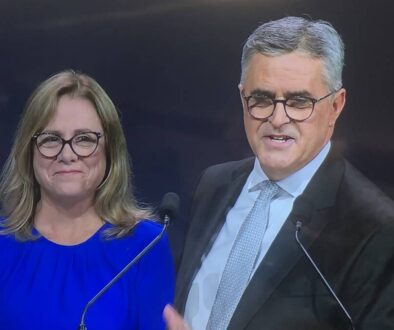

Michael and Lindy Chamberlain: Interview with Historian Milton Hook

January 16, 2017: Many younger Adventists may not remember Michael and Lindy Chamberlain, in spite of the news coverage and the film that made their story familiar to those of us who were alive at that time.

The story: a young Adventist pastoral couple are camping at Uluru / Ayers Rock, a popular Australian tourist spot, in August of 1980, when a wild dog snatches their infant daughter, Azaria. Instead of believing Michael and Lindy, law enforcement charge the Chamberlains with murdering their own baby.

Many people still don’t understand the factors that contributed to the way this story unfolded.

In the wake of Michael Chamberlain’s recent death, AT editor Loren Seibold contacted Australian Adventist historian Milton Hook to answer some questions about the case.

AT: Canids are opportunistic feeders. Why was there such a reluctance to believe that a wild dog would take a baby?

Hook: Because the rangers claimed that a wild dog would not take a baby. The rangers and the Northern Territory government were keen to protect the reputation of the national park as a safe place for tourists to visit and camp overnight. The opinion of the rangers carried great weight with the press and the press shaped public opinion. The rangers were happy for the Chamberlains to be accused of murder, despite that local aboriginal trackers found wild dog tracks in close proximity to the tent and believed a wild dog could and would take a baby.

How did the Seventh-day Adventist identity contribute to the suspicion against Michael and Lindy?

The Seventh-day Adventist identity has always been misunderstood except in areas close to major Adventist hospitals and colleges. Despite an active public relations department over many decades the name Seventh-day Adventist for most people means people who don’t smoke, don’t eat pork and observe the Jewish Sabbath.

The line between public relations and evangelism has always been blurred. Stop smoking programs, stress management programs, vegetarian cooking programs and the like, have never had an altruistic goal. They have been used to search out individuals who may attend a follow up program in Bible prophecy. The general public are quick to see this ill-disguised line and have become gun-shy. They have been left remarkably ignorant of what Adventists really believe. This ignorance has become a breeding ground for rumor and false accusation. That ignorance came to the fore in the Chamberlain case.

The line between public relations and evangelism has always been blurred. Our programs have never had an altruistic goal, but are meant to attract people to a follow up program in Bible prophecy. The public are quick to see this ill-disguised line, so have been left remarkably ignorant of what Adventists really believe. This ignorance is a breeding ground for rumor and false accusation

I recall that there were twisted theological arguments made that contributed to the suspicions people held about them.

The most bizarre one in the melodramatic press was that Adventists engaged in child sacrifice, and that was what Michael and Lindy were accused of doing and covering up. Someone made the claim that the name “Azaria” meant “sacrifice in the wilderness”—it actually means “God helped”. Others pointed to pictures in which, they said, the baby was dressed in black. In order to paint Adventists as weirdos, the church was also accused of opposition to blood transfusions, a clear confusion with Jehovah’s Witnesses and an example of a general ignorance about us that our public relations had not properly addressed.

Did Seventh-day Adventists support the Chamberlains?

Adventists believed the Chamberlains, and many wrote sympathy letters to Lindy (my mother included) when she was jailed. The church administration provided monetary and chaplaincy support. It was an Adventist lawyer who defended them in court. Adventist scientists worked to discount the so-called forensic evidence put forward by the prosecution. This had considerable success in the end, the alleged blood stains in the Chamberlain car proving to be materials used in car manufacturing.

And Adventists understood the apparent stoicism of the Chamberlains. Those not of the church interpreted their stoicism as the reaction of cold calculating killers. Adventists knew it was the reaction of those who believe in the resurrection, a sadness salted with hope.

Adventists understood the apparent stoicism of the Chamberlains, which those outside the church interpreted as the reaction of cold calculating killers. We knew it was they believed in the resurrection, a sadness salted with hope.

How did church people feel through all of this?

We were dismayed by the misinformation in the press that rapidly became widespread throughout Australia. Adventists working in our institutions were largely protected from adverse feelings. Those working alongside non-Adventists sometimes experienced ridicule. Other Adventists kept quiet about their identity.

Was there a public reaction against Seventh-day Adventists? Did it affect the work—evangelism, hospitals, outreach?

There were one or two instances of defamatory graffiti painted on church buildings. I am not aware of any drop in baptismal figures or other adverse evangelistic effects that could be attributed to the Chamberlain case. For much of the time I was living in the shadow of the Sydney Sanitarium and Hospital and I feel certain there was no slide in patient numbers or reputation.

Were there press or public figures who came to the defense of the Chamberlains and the church?

Two pressmen in particular supported the Chamberlains’ claim. Newspaper man Malcolm Brown did so when he weighed the evidence of aboriginal trackers and eye witnesses present at the camp site. He sensed the government and rangers had an ulterior motive. And he doubted the qualifications of the prosecution’s forensic scientists. John Bryson wrote about the case in Evil Angels, sharing Brown’s sentiments alongside with his own. The Chamberlains engaged a publicist, Harry Miller, to counter any bad press and Miller was especially able to influence TV front man, Ray Martin, to present a softer, more humane, aspect to the usual media stories.

There was, however, a downside to the publicist: Miller demanded exclusive rights for his stories. This left most pressmen out of the loop and opened the way for more misinformation.

What was the outcome for the Chamberlains and for the church?

After the trials and imprisonment and appeals and court cases to entirely clear their names, they were exonerated. They paid a lot of money for the exoneration. They were also paid a lot of money in compensation. Their marriage disintegrated. Ray Martin said recently that Michael in particular carried to his grave a deep sense that he had been the victim of injustice and a shoddy legal system. I often spoke with Michael, and agree with Martin’s assessment. My view is that there were no real winners in the whole sad saga.

I think effects on the church were minimal in the long term because the longer the case continued through the courts the more it became about the Chamberlains and less about the church. The bizarre accusations leveled at the church in the beginning faded simply because they were so silly.

What was the effect on Australian society?

The Chamberlain case is forever etched in Australian legal history as one charged with emotion, intrigue, faulty forensic evidence, lack of a body, no proven motive, a disregard for eye witness accounts, and the dismissal of aboriginal knowledge about wild dog spores and habits. It is an unavoidable, even embarrassing, scar on the Australian legal system. The initial prosecution lawyer will be remembered as clever, but not particularly concerned with justice. He was happy to have a win attributed to himself at the expense of an innocent pair—some say a naive couple—at the time. The late discovery of Azaria’s bloodied and torn night attire out in the desert seemed to turn the tide of guilt and eventually favored judicial exoneration.

The Chamberlains did not fade from view. Miller kept arranging public interviews with them. The Chamberlains themselves kept publishing. For that reason most Australians still remember them.

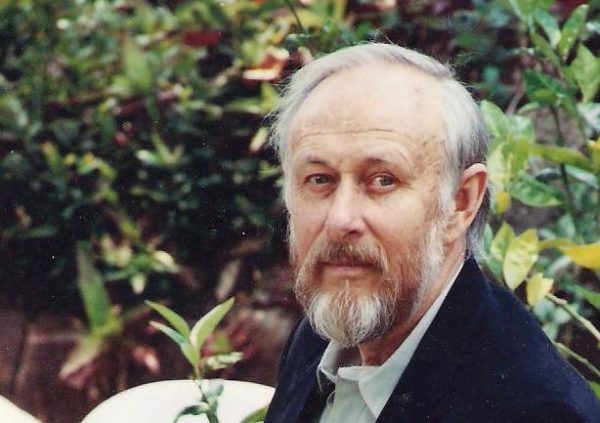

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978) as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new SDA Encyclopedia.

Milton Hook graduated from Avondale College in 1964 and was a pastor in Australia, a missionary in Papua New Guinea, a Bible teacher at Longburn College in New Zealand, and a pastor in the United States, where he earned a Ph.D. in religious education at Andrews University (1978). In retirement he is an Honorary Research Fellow at Avondale College. He is the author of Avondale: Experiment on the Dora (1998), Desmond Ford: Reformist Theologian, Gospel Revivalist, and Flames Over Battle Creek (1978) as well as more than 40 journal articles and monographs on Adventist history. He is currently writing church history articles for a new SDA Encyclopedia.