How Shall We Resolve Congregational Conflicts?

by Mark McCleary

John Donne, English cleric, said, “No man is an island unto himself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the mien.” Donne speaks to the individual and his social context as corollaries. This perspective of social life provides breadth and depth to conflict and its potential resolution.

You’re an Adventist Today reader, but are you an Adventist Today supporter?

Congregational actors, like their secular counterparts, experience conflict over interests, beliefs, power, and more. Such conflicts negatively impact social harmony and ministry effectiveness. It is hope in human capacity that drives conflict interventions and justifies this article’s position that social harmony can be improved by using rational procedures that guide the intervention participants toward mutually satisfying resolution.

The assumption for this article is that if conflict resolution procedures or guidelines exist in Christian churches, they are either unknown or not promoted or used by most congregational leaders and members. This reflects over 39 years of pastoral experience and dialogue with other pastors, church administrators and laypersons, leading to the recommendation of a best practices conflict resolution tool to assist Christian churches and others in conflict resolution know-how.

Goal

Conflict resolution interventions are action-oriented in nature. Many are rooted in Social Science conflict and conflict resolution theories and practices. A serious learner will discover all he or she can on this topic to apply its know-how to a setting. Such discovery is driven by a pragmatic impetus. As pastor, I have witnessed many intra-church conflicts that might have been processed if all parties had awareness of and access to a tool that might help them solve their social problems.

In the remainder of this article, I tell of my attempt to address this lack during my Ph.D. journey at Nova SE University’s Department of Conflict Analysis and Resolution. As a community and church stakeholder, I decided to develop a tool that would be academically and biblically sound for someone interested conflict resolution basics.

Matthew 18:15-17 as Framework for Conflict Resolution

Moreover, if thy brother shall trespass against thee, go and tell him his fault between thee and him alone: if he shall hear thee, thou hast gained thy brother. But if he will not hear thee, then take with thee one or two more, that in the mouth of two or three witnesses every word may be established. And if he shall neglect to hear them, tell it unto the church: but if he neglects to hear the church, let him be unto thee as a heathen man and a publican.

For those who adhere to the Bible as their rule of faith and practice, there has been little to no application of this New Testament passage as a conflict resolution intervention. There are some like Kenneth Newberger (2008), who refers to it as the most “misapplied passage on church conflict”. His conclusions spring from the use of this text as solely a judicial procedure, and that it would tend to escalate rather than resolve church conflict.

It is my opinion that Newberger’s reasoning is myopic. The following analysis of this passage is what I believe upholds its potential for helping its practitioners solve their social problems. It was authored by a Jewish publican, Levi Matthew (Matthew 9:9, KJV), who wrote primarily to a Jewish audience concerning intra-synagogue, intragroup, and interpersonal conflict. According to John Paul Lederach, the chapter is about mundane human relational disparities (Lederach, 2014). Its pre-text reveals a prescription for restoring social harmony that is rooted in an altruistic ethic. The chapter begins with Jesus’s query, “Who is the greatest among you?” Jesus then answers His question by describing non-threatening children as illustrations of Kingdom eligibility. He then warns against inter-brother offenses; and subsequently tells a parable about recovering a lost sheep or group member. His commentary focuses on horizontal relations between social actors and not judicial top-down administrators determining interests, rights, or values between conflicting actors.

At the heart of this passage is trespass. Its connotation includes lying, theft, deception, injustice, or uncharitableness. All these indicate divergence at the interpersonal level of social interaction. Its Old Testament term is asham, which means debt or bill paid and concerns personal and private issues of social relations (read Leviticus 5:14-6:7, KJV). This reasoning asserts that individuals retain the capacity to resolve their problems. Lederach’s summation of Matthew 18 supports my analysis that the primary goal of this text is to work for reconciliation (Lederach 20014).

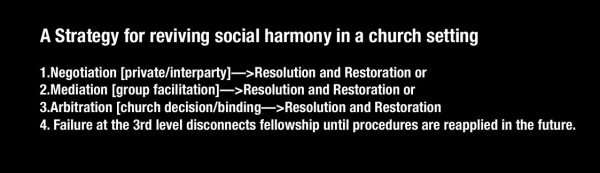

The text prescribes private negotiation as the first course of action for parties in conflict (Matthew 18:15, KJV). It suggests that if reconciliation is not attained here,, community [church-sponsored] mediation is an alternative (Matthew 18:16, 17, KJV). Lastly, if these efforts fail, then a church arbitration approach should be applied. This is what I understand as large-group arbitration and concludes the procedures.

A realistic view of this passage acknowledges that some situations are not resolvable, at least at the time of intervention. In such situations, the text seems imply coexistence between former allies—one now in, and the other outside of, church fellowship.

Nor is this necessarily a failure. I view Matthew 18:15-20 as a practical formula for dealing with conflict without coercion, until all else fails.When it does, then “treat him [the irreconcilable party] like a heathen” (Matthew 18:17). This does not mean active conflict, but conflict management by trying to reclaim this heathen. Are not heathens worthy of church mission and reclamation activity?

Conclusions and Recommendations

Ignorance or a do-nothing attitude are insufficient reasons for living with social conflict. I have developed a manual that provides hope for individuals and groups seeking to reestablish harmony in place of alienation and divergence, which I am willing to use to assist you in conflict situations. Over my 39+ years as a pastor, nothing related to conflict resolution has been broached in a formal and official manner within the churches I have encountered. A workable conflict resolution procedure would assist in conflict resolution for congregational and secular organizations. Please contact me if I can be of help to you.

References

Lederach, John Paul (2014). Reconcile: Conflict Transformation for Ordinary Christians, Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press.

Newberger, K. (2008). Matthew 18:15-18: The most misapplied passage on church conflict, Retrieved from www.resolvechurchconflict.com/church_discipline_matthew_18.htm.

Mark McCleary is the senior pastor of the Liberty Seventh-day Adventist Church in Windsor Mill, MD. He’s earned a D.Min from Palmer Theological Seminary, and Ph.D. in Conflict Analysis from Nova Southeastern University. He and his wife Queenie have been married for over 40 years, and have three grown children.