Christ the Eschatos: A Meeting with GNU and the General Conference

by Smuts van Rooyen | 14 March 2019 |

A good while after Glacier View—I forget how long—Elder Duncan Eva from the General Conference (GC) suggested a meeting with the purpose of effecting reconciliation between the denomination and Good News Unlimited (GNU, the new ministry set up for Des Ford) to take place in San Francisco. He also proposed that each group present formal papers about the prophetic issues. At first we at GNU were very skeptical about the idea. We suspected that the brethren were simply trying to create cover for themselves because of the criticism they were getting from the field.

But we had immense trust in Duncan Eva, great confidence in our own theological positions, and even a confused hope for reconciliation. We agreed to the meeting.

As I recall, the folks on the GC team included Duncan Eva (General Vice President of the GC), Neils-Erik Andreasen (at that time with Loma Linda University), William Johnsson (Andrews University, at the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Theological Seminary), Robert Spangler (editor of Ministry), Richard Lesher (Biblical Research Institute), and Gerhard Hasel (SDA Theological Seminary Dean). They were intelligent and decent people who showed no malice toward us, except for Dr. Hasel. I remember sitting at the rectangle of tables in the conference room at one point thinking, “This is surreal—these are my people, my brothers. How did things ever come to this?”

Our group included Des Ford, a brilliant theologian and newly coronated heretic; his wife Gill Ford, a biblical scholar in her own right; Calvin Edwards, a bright researcher and administrator fresh from the seminary, and wise beyond his years; Noel Mason, the most widely read, self-taught, and honest man I know; and myself. Our team was not defiant but certainly determined to make our evidence carry the day.

Upon our arrival at the hotel in San Francisco in the late afternoon, we found the drive to the registration office blocked by a group of ten or so picketers carrying large, handwritten placards. They seemed hot with animus as our driver slowly navigated the car through them to the office. At first we thought they were union workers demonstrating against the motel chain, but soon realized that their beef was with us and the GC. Their signs expressed sentiments like, “No Secret Meetings With Des Ford” “Don’t Compromise The Truth” “General Conference Sells Out” “Resist This Heresy.” How these demonstrators knew about the meetings is anyone’s guess.

At the registration desk the hotel manager pleaded with us to tell the protestors to go away, since nobody besides us had checked in. “Everybody drives by—you’re killing my business! Tell these people to leave,” he complained. We adroitly referred him to Elder Eva, who somehow managed the situation. But this was not the end of the matter.

When we met the next morning, our first session was suddenly disrupted by an individual who, with the zeal of the prophet Elijah at Carmel, burst in to the conference room and demanded, in the name of Jesus, that we immediately desist from proceeding with this sinful gathering. Unintimidated, Elder Eva rose from his seat, told the person that he did not represent Jesus, took him firmly by the arm, and escorted him out of the room.

After a deep breath and a sip of water we proceeded to discuss matters—but the tension remained. This may have been an omen of the failure to come.

I cannot possibly give a detailed account of the full proceedings, and so delimit the discussion to my assignment alone. My task was to address the question, “What Is Eschatology and Why Is It Important?” I considered this charge to be providential because I had studied this very subject with Adrio König at the University of South Africa (UNISA) in great detail. When Andrews University dismissed me from employment I was completing the Th.D program at UNISA—but quit in despair. It was the biggest mistake of my life. Now, I thought, perhaps I had a small opportunity to salvage something from my studies.

But there was more. Over the course of the time that I’d been working at GNU I’d found the ongoing prophetic discussion we were engaged in to be important—it had to be done—but utterly unfulfilling. Debates on the year-day principle, whether Dan 8:14 speaks of cleansing or vindication, Antiochus Epiphanes versus the papacy, the necessity of using the solar-lunar calendar of the Karaite Jews for calculation purposes, the Shut Door, and other matters of hermeneutics are of genuine significance but, in my view, not vital, which is to say, life-giving. I just wanted the music back. I wanted Jesus to be explicit in our eschatological deliberation.

So when my turn came on the first day of the three-day event, I was eager to propose that eschatology is not about future obsession, doomsday clocks, or prophetic charts. Rather, eschatology is the study of every phase of the end of the world as it is revealed in the life of Christ. It begins with the inauguration of the Kingdom of God at his birth, and ends with the consummation of the kingdom at his second coming. In fact, it may not be defined as a simple time category, because it is primarily a person category. The New Testament writers saw the end of time as being their day precisely because the Messiah had arrived. He was to them, in his very Being, “the last,” ho eschatos (Rev 1:17; 2:8; 22:13). He was to them in his very Being, the Alpha and the Omega (Rev 1:8,11; 22:13). The Kingdom of God had come because the King had come.

So, for example, when Martha defined the resurrection as a future event when her brother Lazarus would be resurrected, Jesus immediately challenged her inadequate view of eschatology and asserted, “I am the resurrection!” and promptly raised him (Jn 11). Resurrection could occur without a lapse of time. Time was secondary—the person of Christ was primary.

Perhaps the clearest evidence that the life of the Messiah was the eschatos is seen in connection with demonology. The Jews believed that when the kingdom of God would come Satan would be defeated. Here was a deep eschatological hope. It is not surprising, then, that Matthew sees in Christ’s treatment of demons a conclusive evidence that the Kingdom of God has already come. He records the startling words of Jesus to the Pharisees: “But if I cast out devils by the Spirit of God, then the Kingdom of God is come unto you.” (Mt 12:28) The demons react by collapsing in powerlessness and screaming in fear.

All of this, I argued, has definite implications for our Adventist mission, our soteriology, and our ethics.

In terms of the mission of our church we are to preach “this gospel of the kingdom” (Mt 24:14) if we want to usher in the second coming. This gospel is a particular message encapsulated within the entire life of the king of the kingdom. Christ is the eschatos. But Adventism had defined a unique message for itself, and done so by means of its own nineteenth-century history. With tunnel vision we saw our purpose as the proclamation of a “last warning message.”

But if we are serious about actually heralding the second advent, we would focus on the kingdom. Our joyful vocation would be to proclaim Christ’s parables (that often begin with the words “for the kingdom of heaven is like”) to others. Our aim would be to show how people like Nicodemus, the thief on the cross, the prodigal son, and a host of others entered the kingdom. Our purpose would be to reveal the principles of life in a kingdom that is already here. The particular gospel Jesus wants us to preach is “this gospel of the kingdom.” And yes, we also declare our yearning and groaning for the second coming, when Jesus will receive us to himself.

This eschatology also transforms the way we think of salvation. Because Christ is the eschatos it is possible for the end to be reached (albeit in a limited way) before the natural history of our planet comes to a close. We can get the verdict of acquittal for the coming judgment now (Rom 5:9-11). Moreover, those last day events that have threatened the Adventist equilibrium for so long are neutralized, because they are merely a recapitulation of the history of Jesus. He has been through the last days already, and his success is our success. He’s been through the great time of trouble in Gethsemane, he’s been judged on the cross, he was raised from the dead and lives forever. Thus for us, the end has happened in the person of Christ and we have already been saved from the wrath to come, if we remain in him.

How and why we become good people is also determined by Christ the eschatos. While it is true that we are motivated to live godly lives by our anticipation of the second coming, the fundamental force that excites the Christian to act ethically is the realization that the kingdom of God has come and it is our treasure (Mt 13:44 -46). Moreover, the document informing our morality is the Sermon on the Mount—it is the very constitution of the kingdom. Believers become deeply ethical when they embrace the blessings laid out in the Beatitudes. They are the be-happy-attitudes (Mt 5-7). A new obedience is afoot.

When I’d finished presenting my document with temperate urgency, there was no spontaneous applause that followed, nor the singing of the doxology, but only the subdued clearing of a few throats and some innocuous comments. In fact, the general response to all of our papers was a studied indifference. The GC group did not seem to take us or any of our evidence seriously. We were playing tennis with someone who never returned the ball.

Not even Des’ paper on “The Nature of Old Testament Prophecy and Hermeneutics”—an outstanding presentation that included an appendix by the Baptist scholar Dewey Beegle—evoked much discussion. This appendix was in fact a devastating critique of Gerhard Hasel’s justification of the traditional Adventist interpretation of the seventy weeks of Dan 9:24-27. Hasel was, I think, deeply embarrassed. And when we sent a note of complaint to Elder Eva that his team did not take our evidence seriously but “simply blinked and went on,” their group called off the the third and final day of deliberation, and the gathering abruptly terminated.

A few weeks later a General Conference committee of some sort voted to withdraw the ordination of both Des and me, with the enjoinder that we were never to be reinstated to denominational service “regardless of repentance and reformation.” But that is yet another story.

To read the entire paper on eschatology that I presented at that meeting, click here.

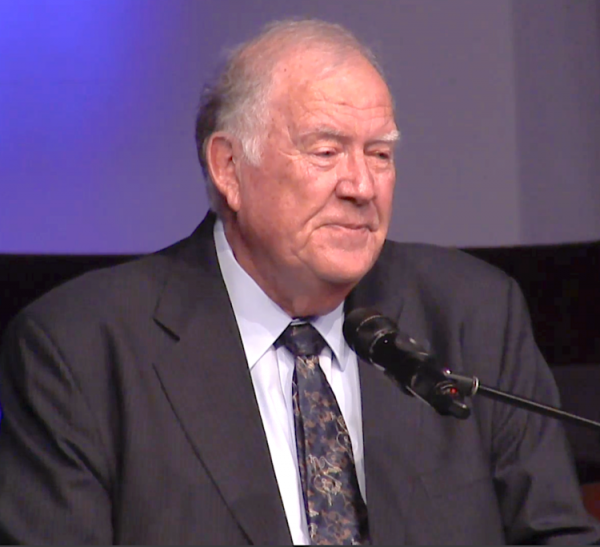

Smuts van Rooyen is a retired pastor living in Central California. He holds an M.Div. and a Ph.D. in Counseling Psychology from Andrews University. His ministry was divided between teaching undergraduate religion and pastoring. He retired as the pastor of the Glendale City Church. He has been married to Arlene for a long time.

Smuts van Rooyen is a retired pastor living in Central California. He holds an M.Div. and a Ph.D. in Counseling Psychology from Andrews University. His ministry was divided between teaching undergraduate religion and pastoring. He retired as the pastor of the Glendale City Church. He has been married to Arlene for a long time.