Book Review: Adventist Mission in the 21st Century

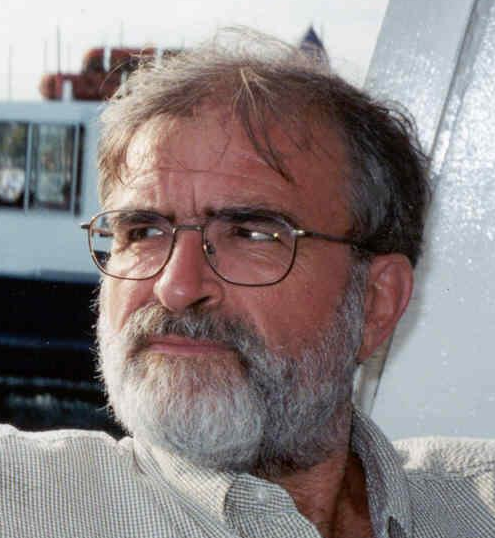

by Ronald Lawson, Ph.D. | 14 April 2019 |

A review of Jon L. Dybdahl (ed.), Adventist Mission in the 21st Century. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald. ISBN 0-8280-1339-X

Originally published in Review of Religious Research, 41(3), March 2000.

This book, edited by the chair of the Department of World Mission at Andrews University, home of the Seventh-day Adventist Seminary, with contributions from 30 scholars, administrators, pastors, teachers, and laypersons involved in cross-cultural missions and drawn from all continents, assesses the state of Adventist missions and the issues facing them. The book is divided into four segments: an overview of the themes, biblical and theological issues, strategies and methods, and case studies. Since both Adventism and its approach to mission are experiencing profound changes, it is not surprising that the contributions sometimes conflict with one another – but insights emerge from the conflicts and accounts of change.

Although Seventh-day Adventists, whose roots go back to 1844 and the Millerite Movement in the American northeast, believed they were called to take “God’s last warning message” to the world, the task seemed overwhelming to what was initially a tiny group. Consequently, they did not send out their first foreign missionary – to Europe – until 1874. After that initial step, missionaries were commissioned with increasing frequency during the subsequent quarter century until the restructuring of the denomination in 1901-1903 had the effect of turning Adventism into a worldwide mission society – a focus that was initially embraced enthusiastically by the membership. The mission program was built on a strong financial base, rooted in a system that directed funds upwards from congregations – especially American congregations – to the central church administration. These funds were used to replicate the institution-oriented pattern that had already been established in the US, with educational, medical, and publishing institutions. These became the cornerstones of Adventist outreach and the conduits for upward mobility among converts. However, they also made the church in the Developing World a large employer dependent on a flow of funds from the Developed World. Moreover, the ready availability of such funds, the quality of buildings, the relatively ostentatious housing and lifestyles of the missionaries, and the middle class salaries paid to national pastors and administrators discouraged financial stewardship among the mostly poor converts in the mission lands.

Although Adventists came late to the mission movement of the nineteenth century, they, in common with Christianity as a whole, have experienced the shift in the demographic center of gravity from the Developed to the Developing World in recent decades: as a result of a sharp increase in their growth rate in the Developing World during the past three decades while growth lagged elsewhere, more than 85% of their 10 million members were located in the Developing World in 1998.

Meanwhile, however, the number of missionaries supported by the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists had fallen sharply, from 1,546 on 1973 to only 676 in 1993. This decline was not typical of the experience of other Protestant churches during that time, when attention was generally shifting from a country-by-country approach to one focusing on unreached people groups: for example, during this same period the number of missionaries supported by the Southern Baptist Convention increased from 2,507 to 3,660. Consequently, Adventists slid from fourth in size among the Protestant mission agencies in North America to tenth during that period. With fewer cross-cultural missionaries, many Adventists lost the close connection they used to feel to missions. Giving by North American Adventists to the official church mission program plunged, from $125.73 to $22.25 per capita between 1950 and 1990 as measured in 1982 dollars. As the funds available to Adventist missions were stretched ever tighter by the decline in giving and the disparity in growth between the Developing and Developed Worlds, the world church was forced – often painfully – to become less dependent on North America for both funds and personnel, with each region caring increasingly for itself.

However, the last two decades have seen the emergence of a large number of independent mission-sending organizations, whose focus is typically on church planting rather than institution building. Church leaders were at first very wary of these because they were used to being in total control, but have come gradually to view them as allies rather than rivals. While most of these organizations are headquartered in the US, some are located elsewhere, especially in the Philippines.

There have also been a number of new mission initiatives, often borrowed from other missions. These include Global Mission, whose goal is to plant churches among unentered peoples; a tentmaker program, where professionals with missionary commitment take secular jobs which allow them legitimate entry to unentered areas where designated missionaries would not be admitted; and a variety of opportunities for students and other volunteers to participate in various short-term mission activities. Although the Adventist Student Missionary program, which places students from Adventist colleges in mission positions for a year, is small compared to its Mormon counterpart, it now places more than 500 students per year.

The Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) has also created a strong presence since 1980. It utilizes funds from various governments and governmental agencies, such as USAID, to help communities provide food, water, shelter, medical care, and roads to meet their physical needs. Active in 143 countries, ADRA is now one of the largest nongovernmental organizations of its kind in the world. Adventists argue that acting with disinterested love to help the poor, oppressed and marginalized is part of their mission because God is concerned not just with the soul but with the whole person, and people cannot focus on their spiritual needs until key physical needs have been met. Although the philosophy of ADRA is to do good for the sake of doing good, expecting nothing in return, its approach has brought credibility to Adventism and opened doors, allowing it to become active in situations where a traditional Adventist presence would not have been possible.

Meanwhile, Adventism has embraced technology. This pattern dates from the realization of the potential of radio for evangelism in 1935, and the founding of one of the first religious broadcast programs. Today the Adventist Church owns and leases shortwave radio stations which beam broadcasts in 45 languages and for more than 1,000 hours per week into regions where Adventism is poorly represented. Beginning in the mid-1990s, it linked churches all over the world by satellite, and has transmitted several polished evangelistic series featuring simultaneous translation as needed. In spite of the limitations of this one-size-fits-all approach to evangelism, the technology has drawn large audiences, especially in parts of the Developing World.

While most Adventist mission work today places personnel in institutions serving the Church where it already exists, many of these more recent initiatives attempt to focus more on areas where it is not yet well established. Their protagonists hope that these changes are signs that the colonial era of missions has passed and is being replaced by a truly international era, when missionaries from everywhere will go everywhere, especially to the unentered people groups. However, the hierarchical, highly articulated, five-level (from congregations to General Conference) structure of the Adventist Church hinders broad participation in mission. The emphasis on the need of institutions for highly skilled personnel, and the facts that most calls to service are from entities where Adventists are concentrated and there is no General Conference mission department coordinating the mission enterprise and promoting the needs of unreached areas, has created a system that rarely encourages the entry of North American youth into mission careers or provides a conduit for members in the Developing World to serve outside of their own regions.

Nevertheless, missiologists and theologians are grappling with two new issues which suggest that further major changes in Adventist mission are under way. The first asks how Adventists are to view the non-Christian religions. The other major world religions were typically ignored by Adventists in earlier decades because they were not mentioned in their end-time scenarios: their evangelistic thrust was aimed primarily at other Christians, although they were often successful also among animists. However, the new concern for people-groups where Adventism is not established, which are found especially in the zone lying between 10 and 40 degrees north of the equator – the world of Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and the Chinese – has forced Adventists to turn their attention to population groups where the non-Christian world religions are not only dominant but are also resurgent. Contributors address new approaches among both Muslims and Buddhists, as well as an unexpected turnaround in China, where new kinds of grassroots Adventism have emerged.

Conventional Adventist missions have converted very few Muslims, and converts have usually faced exclusion from their communities. However, a new, more sympathetic, approach has been developed which has been successful in creating a nucleus of 2,000 “contextual Adventists” within an unnamed Islamic community. Those utilizing the new approach denounce nothing within Islam and seek to build credibility within the Muslim community as godly, prayerful persons who are followers of the Book and of Allah and are caring neighbors. In their interactions with their neighbors, these “change agents” build spiritually on the insights of Islam, avoiding doctrinal discussions and arguing about Christ, waiting instead for insights to occur: the object is a deeper faith rather than an announced change of faith. Those who become followers of Jesus continue to worship in the mosque as well as meeting with one another (presumably on the Sabbath), when they also use Muslim forms of worship, and thus avoid being declared apostate. Meanwhile, the many young Muslims scattered over the Middle East and North Africa who have responded to the new Adventist radio programs there have been formed into a listeners club as a means of keeping contact with them, with over 1,000 joining in the first year.

Similarly, very few Buddhists have been converted to Christianity or Adventism until recently. However, more than 12,000 Buddhist Cambodians were baptized in refugee camps in Thailand between 1979 and 1993. Whereas before that time there was only one Adventist church in Cambodia with fewer than 30 members, there are now 77 congregations with thousands worshiping. A Study Center for Buddhism in Bangkok, where the director dresses in Buddhist garb and engages in interfaith dialogue with Buddhist monks, has also been successful in making many converts. A new contextualized approach to the Buddhists in Myanmar, the brainchild of a former renowned Buddhist nun, which will use local art forms to depict the life of Jesus and draw both parallels and contrasts between his life and that of the Buddha, is being prepared.

Adventist missions entered China in 1902, and by 1950 Adventism had established its typical hierarchical, institution-oriented structure, with 15 schools, 16 hospitals and clinics, a publishing house, several hundred church employees, and 23,000 members. However, the Communist revolution resulted in the expulsion of all missionaries, the loss of the institutions and the dismantling of the structure, and the end of public evangelism. It seemed as if the missionary-dominated church had died. However, following the emergence of the post-denominational Three-Self-officially-tolerated Christian movement in the 1970s, Chinese Adventists used their belief in observing the Sabbath on Saturday as a means of gaining separate worship services. Those members whose earlier apparent commitment was based on their desire for jobs in the Adventist institutions have been sifted out, leaving an indigenous, committed, laity-led church which has expanded through interpersonal evangelism and the establishment of many house churches. Reports indicate that its membership is now over 200,000. Tentmaker missionaries have helped to restore unofficial ties to the world church.

The second new issue is to what extent Adventist belief and practice can be adapted in order to communicate with people of other cultures. Adventists have become aware that their early missions carried American culture with them, established centers of such culture in institutional and administrative compounds, and often consciously separated converts from their own cultures and peoples. There is now a much greater realization of the need for contextualization of what is taught, with careful training of would-be missionaries to this end by the Institute of World Mission. However, the centrality of Adventist doctrine limits this because a commitment to the 27 Fundamental Beliefs of Adventism is taken for granted, even though many pastors and teachers in Developing Countries have explained to me that, for example, the complicated sanctuary doctrine and its long prophetic time spans are beyond the understanding of many of their members.

One contributor argues that the reason why Seventh-day Adventism far outstripped the other five groups that emerged from the Millerite Movement after the failure of Miller’s prediction that Christ would return in 1844 was that it alone retained a strong sense of having a special God-given “end-time” message of warning to deliver to the world which provided it with motivation. However, that motivation is now flagging as many members, especially in the Developed World, are embarrassed by their church’s claim to have a special status, and the message seems dated and its content increasingly blurred. The editor hints at this when he refers to Adventism’s openness to new technology but its reluctance to repackage its message in a form that will communicate beyond Bible-believers, who have long been the typical Adventist converts, to the vast secular population of the world. However, he does not mention the uncertainty of what the basic thrust of that special message should be more than 150 years after Adventists began to proclaim that the return of Christ was imminent; nor does he speak to the problems caused to the faith of members who have been taught that the Adventist message must be preached to the whole world before Christ can return by the switch in measuring progress in this from the proportion of countries in which Adventists have established a presence (which showed the task almost done) to people groups (where large numbers are still unentered).

The disparate messages within Adventism today may be discerned in the conflicting voices among the contributors. While one celebrates Adventism’s traditional prophetic message, another tells of the extraordinarily high apostasy rate among the converts of the American evangelists who proclaimed that message within the former Soviet Union after the fall of Communism; while one rejoices in ADRA’s doing good with no strings attached, he admits that other Adventists see this as a betrayal of Adventism’s special calling; while one assumes a doctrinal and cerebral emphasis with no bending of Adventism’s 27 fundamental beliefs, the new approach among Muslims avoids doctrinal teaching and debate, and another would renew mission through an emphasis on healings and miraculous signs; while some declare that the purpose of the Adventist message is to proclaim the imminent end of the world, another celebrates the radical political and social impact of the pioneer Adventist missionaries to the Peruvian Highlands; while several see the core of the Adventist message as the proclamation of the good news of salvation through acceptance of Jesus Christ, others see God’s saving all sincere religious seekers–even if they have never heard of Jesus, no longer equate the other world religions with heathenism, and have adopted an approach which, in order to reach Muslims, does not proclaim the deity of Christ and where converts avoid identifying themselves as Christians.

Ronald Lawson is a lifelong Seventh-day Adventist, and a sociologist studying urban conflicts and sectarian religions. He is retired from Queens College, CUNY.

Ronald Lawson is a lifelong Seventh-day Adventist, and a sociologist studying urban conflicts and sectarian religions. He is retired from Queens College, CUNY.