Your Existence Is Political: The Privilege of Neutrality

by Rebecca Brothers | 16 January 2020 |

Last year, I signed up for a class at my church.

The class is called “Education for Ministry.” It’s a four-year program coordinated by an Episcopal college, the University of the South. First-year EfM students study the Hebrew Scriptures; second years, the New Testament; third years, Christian history; and fourth years, theology, ethics, and interfaith relations.

By the end of your four years in EfM, you should (ideally) have a good understanding of your faith and its biblical, historical, and global context. You should (ideally) have an idea of how to fulfill your call to a specific vocation or ministry.

I had my first EfM class in early September. It was fairly standard: The leaders explained the schedule and introduced the textbooks.

“And one more thing,” our leader said. “No politics during discussions.”

I have followed this rule in class, but it got me thinking about our proclivity for “no politics” zones. It made me wonder about the line between “personal” and “political,” and how thin and ever-shifting that line is. It made me think of the many people I have encountered who say they’re “not really into politics.”

I have followed this rule in class, but it got me thinking about our proclivity for “no politics” zones. It made me wonder about the line between “personal” and “political,” and how thin and ever-shifting that line is. It made me think of the many people I have encountered who say they’re “not really into politics.”

I used to be one of those people. I don’t remember why. Maybe I felt helpless to effect change; maybe I didn’t see the point of getting involved in “someone else’s” fight. Probably both of those things were true.

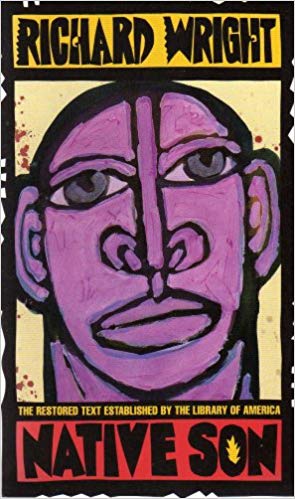

Then I learned about privilege, and how much of it I have—how many fewer hurdles I face in life’s race simply because I am white, educated, cisgender, and able-bodied in a society that gives priority to all of those identities. This lesson first impacted me when I was assigned to read Richard Wright’s book Native Son in college. I’m going to spoil the book for you: The protagonist, a 20-year-old Black man named Bigger Thomas, accidentally kills a white woman and goes on the run from law enforcement.

As I read Native Son, I was thinking, “Why doesn’t he just turn himself in and explain the whole situation to the police? I’m sure they’d understand.”

And then, during his lawyer’s impassioned speech at his trial, I realized, “Oh … that wasn’t an option. Bigger didn’t have much of a chance at escaping from the police, and he didn’t have much of a chance in the legal system. Since he was born, he’s been trapped in this system that’s biased against him — and his ancestors have been similarly trapped for generations.”

After that, I started making a conscious effort to step outside my majority-white, majority-straight, majority-able-bodied, majority-Christian spheres and learn from people who represent some sort of minority—or an intersection of minority traits. As I did this, I started to realize that for some of my friends, existence is political—just like it was for Bigger. To this end, I think of my friend who is a gay female disabled rabbi. I think of my friend who is a Palestinian Muslim, my friend who is a disabled trans woman in Northern Ireland, and my friends who are Muslims in India and Christians in Egypt.

None of them have the luxury of being apolitical. Their presence in society has been criticized, mischaracterized, demonized, and sometimes simply ignored. My friends have to get political if they want access to public restrooms, traffic stops that go smoothly, fair treatment in the legal system, or the courtesy of personal pronouns that match their identity. These are not new problems for them and their communities, but the rest of us are still catching up on what their reality looks like.

In a happier world, it would not be controversial to admit that the problems other people face based on some facet of their identity are real and serious. It would be a straightforward matter to admit that “Equal rights for others does not mean fewer rights for you. It’s not pie.” It would be a matter of course to acknowledge others’ existence, instead of our habit of covering our ears and singing, “La la la, I can’t hear you, you’re not really there.”

But we privileged folks are rather good at indulging that habit. We’re good at pretending that there are no gay or trans folks in our churches or schools, so there’s no need to speak about them like they’re real human beings worthy of respect — much less enact policies that respect their dignity and rights. We’re good at pretending that our facilities don’t need accessible doors and ramps and bathrooms, because “That’s never been an issue before.” We’re good at getting defensive and turning discussions of privilege into games of one-upmanship. We’re good at forgetting that, as one person put it, “When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.” We’re good at elevating individual voices that say, “I’m a member of that minority group, and I don’t see any need for change” — voices that confirm our own beliefs and don’t force us to look at the broader, more prevalent patterns of discrimination present in that community.

When we say “I’m not political,” we speak from a place of privilege. We assume that all people are as well insulated from the effects of public policies as we privileged folks are. We take for granted the rights we enjoy as the result of our forebears’ campaigning—or, if we do make an effort to appreciate those rights, we often stop short of wondering, “How can I help make these rights accessible to others who don’t have them yet?” And all too often, we focus exclusively on meeting people’s immediate needs—shelter for the night, a warm coat, a hot lunch — but stop short of advocating for the policies and legislation that would help those people in the long run. Somehow, that kind of action is “too political.” When courts and city councils and state legislatures are involved, we’re out.

So this is my challenge to you: Be political on behalf of those who don’t have the luxury of being apolitical. See your facilities and your city through the eyes of the disabled, and fight alongside that community for necessary changes. Take the pain you feel on behalf of Christians in minority-Christian countries, and translate it into fighting for the rights of Muslims in minority-Muslim countries. Seek out immigrant voices, listen to their concerns, and work with them to preserve their rights and dignity. Learn to spot “hostile architecture”—public design elements, like spikes, that seek to discourage the presence of homeless people — and spur public conversations about what such architecture says about our priorities and values as a society.

We privileged folks have a duty to amplify the concerns of those who are running the same distance with more hurdles. We have a duty to constantly examine how the world around us was built with us in mind—and use those realizations to act on behalf of those who can’t navigate that architecture and systems and processes as easily as we can. We have a duty to get political when others’ rights and dignity are under attack, because political actions might be the only thing that will save them.

This work will be messy and uncomfortable. It will force us to step away from our instinctual identities as NIMBYs (that is, people who say “Not In My Back Yard”), and instead lean into proposals to build homeless shelters and soup kitchens and addiction rehab clinics in our neighborhoods. This work will make us re-examine how we prioritize property values and social standing. It will make us re-examine our understandings of gender and poverty and race.

But what use is a Gospel that doesn’t turn our worlds upside-down? What use is a Gospel that doesn’t compel us to see Christ in the hungry, the thirsty, the sick, the naked, the prisoner, and the stranger?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

Friends, we are in the middle of history being made. We are seeing so many elephants put their feet on the tails of innumerable mice. What will we do? How will we respond?

Rebecca Brothers is a graduate of Lincoln City Seventh-day Adventist School, Walla Walla University, and the University of Washington. She is a happy member of the Church of the Nativity in Huntsville, Alabama, and currently works as an academic librarian. Her proudest achievements include serving as a student missionary in Podkowa Leśna, Poland, and being completely submerged in mud during sixth-grade Outdoor School.

Rebecca Brothers is a graduate of Lincoln City Seventh-day Adventist School, Walla Walla University, and the University of Washington. She is a happy member of the Church of the Nativity in Huntsville, Alabama, and currently works as an academic librarian. Her proudest achievements include serving as a student missionary in Podkowa Leśna, Poland, and being completely submerged in mud during sixth-grade Outdoor School.