The Ghosts of Adventism

by Seth Pierce | 9 October 2018 |

I have a confession to make: I believe in ghosts.

Now, I also believe our teaching of conditional immortality. The ghosts I’m talking about operate on a metaphorical level.

Even that may be too scary for some. I once used a football analogy that resulted in an angry letter from a physician declaring, “Our modern prophet has stated football has become a school of brutality and that Satan uses it to nullify the work of the holy Spirit” (Gleaner, June 2015). One can only imagine if I had used a metaphor from boxing. C.S. Lewis also received criticism from a doctor for using a mathematical metaphor to illustrate the Holy Trinity. Lewis reflected:

I could have understood the Doctor’s being shocked if I had compared God to an unjust judge or Christ to a thief in the night; but mathematical objects seem to me as free from sordid associations as any the mind can entertain (God in the Dock).

Just remember that provocative metaphor seemed to fit well within the practices of Jesus.

The ghosts I’m talking about operate beyond metaphor, into the realm of what Blackman calls “structure of feeling” (Affective Methodologies). Affect theory explores atmospheres of feeling and how they shape our pre-cognitive responses to various environments. Like the feeling of being haunted. Before discussing the ghosts themselves it is of grave importance to spend a few moments discussing the logic of haunting.

Hamlet & Hauntology

In Spectres of Marx (1994) Derrida develops a logic of haunting that he applies to Marxism and late Capitalism. He invents the term “hauntology,” a play on the word “ontology” which is the study of being. Hauntology suggests that our present is haunted by pasts and futures that never happened (Fisher, Ghosts of My Life). Loevlie (2013) calls this an “ontological quivering”—a place of in betweenness, which relates to a similar concept discussed by Derrida—spectrality. Defined here, spectrality is a felt absence related to trauma and memory. Simply put, some traumas of the past often come back to haunt us in the present.

To illustrate, Derrida cites a line from a ghost in Hamlet who has returned seeking justice, declaring, “The time is out of joint.” A work of mourning must be done to try and bring the time back into “joint” to foster healing. This logic of haunting can be seen in most ghost stories such as Dickens’ classic A Christmas Carol, where ghosts of time work on Scrooge to bring him to repentance. Ellen White even tells a story about a man whose youthful days “came back to his memory like reproachful specters” (Youths Instructor, 1881). I have been wondering: does Adventism experience an “ontological quivering?” Do we have traumas that meddle with our mission? These questions led me to a great disappointment.

The Great Trauma

Seventh-day Adventism began in tears.

When Jesus failed to return on October 22nd, 1844 the words of Hiram Edson capture the experience of the disappointed believers vividly:

Our expectations were raised high, and thus we looked for our coming Lord until the clock tolled twelve at midnight…Our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us… It seemed that the loss of all earthly friends could have been no comparison. We wept and wept, till the day dawned.

The midnight cry became crying at midnight. This was the spiritual trauma our church was birthed in—and it haunts us.

Arel (2016) suggests that, “Trauma is not just an event that happens at once and disappears. Instead, trauma resides in the body as affect and has residual effects at varying degrees” (Post-traumatic Public Theology, p. 181). Our church body revisits this trauma each October with Adventist Heritage Month, designating the 22nd as The Great Disappointment, and posting memes with phrases like, “Happy Theological Humility Day.”

However, a more striking example was released by the General Conference in 2015 shortly before the General Conference Session. The video, hauntingly entitled What Might Have Been, re-enacts the 1901 General Conference Session. Throughout the film various historic personalities mourn a lack of faithfulness that delayed the Second Coming. Note a couple of the lines:

- “This delay is our fault…my fault…” ~ Bro. Daniells

- “It. Is. Our. Fault. We have let God down.” ~ Bro. Irwin

From here the movie shifts to scenes of humility, repentance, and fellowship at a General Conference session—scenes that remain only in Ellen White’s visions, but never materialized. The Second Advent, again, fails to happen—leaving the time “out of joint”.

Because we feel that we failed our mission in the past, we have postponed a future we have desperately desired to be present. For over 170 years. Adventism is haunted by a past that never happened and a future that hasn’t happened yet. As Knight points out, “Time is our greatest problem” (End-Time Events, 2018).

Holy Ghost King

The film pivots to present-day with various leaders lamenting how they thought they would be “home” by now. Ted Wilson appears at the end and tells the viewer, “We can look back at what might have been or look forward to what can be.” If we just do what is right, Jesus can finally come. What has been ghosted from the historical narrative in the film is Ellen White’s words at the 1901 General Conference Session to church leadership.

The 1901 Conference that What Might Have Been alluded to featured a sermon by a reluctant Ellen White. The church organization had become unwieldy and ineffective in its empowering of ministers. It had become a place where a few had power over the many, even “manipulating” the system. Ellen gives a clarion call for everyone to “come to his senses” because “we are just about the same thing as dead men” (MS 43c, 1901).

She says, “It frightens me because that I saw unless there was more tenderness, more compassion, more of the love of God” Jesus would “remove the candlestick out of its place” (Ibid). She concludes with a calling for the people to come together in words that seek to heal the traumas and shame that haunt our mission:

“…we cannot reform ourselves by putting our fingers on somebody else’s wrongs and think that is going to cover our own. God says we must love one another. God says we must deal justly, honestly, and truly with one another. God says, ‘I hate your false weights and your false measures.’”

Do we still clung to false weights and measurements when it comes to who is approved to minister and who is not? In 1901 Ellen called for more committees in order to share leadership and empower more ministers to enter the field. Today we have five committees seeking to create restrictions. The ghosts of the past still haunt.

Ellen, speaking before the leadership of the church, says, “Now from the light that I have, as it was presented to me in figures: There was a narrow compass here; there within that narrow compass is a king-like, a kingly ruling power.” Ellen says that God wants us to remove kingly power because, “He wants the Holy Ghost king.” While What Might Have Been warned us of our personal failures, it did not name the specter of “kingly power” as an organizational failure. And for those of us who attended the 2015 GC Session, the presence of the Holy Ghost king was overshadowed by a spirit of triumphalism that sought to crown a winner of a debate instead of making room to recognize all those who work for Jesus. And the ghosts of the past continue to cry out for justice, like souls from underneath the altar (Rev. 6:9). They won’t leave us alone.

Sadly, our denominational dynamic often refuses to speak to the specters, instead favoring the manufacture of more ghosts.

Specters of Faith

Monsters adorn advertisements for our message in order to interest those who already have a fascination with such terrors. True, the visions of the apocalypse are from Jesus and the monstrosities therein provide a scathing commentary on abusive power. Yet, how we choose to arrange those images can foreground phantoms while ghosting Jesus. An evangelistic adage says, “You keep them how you catch them.” Once the beasts have been tamed we create other monsters to keep people close.

Not having the benefit of an eternal hell to frighten people with, we have instead patched together presentations that feel like scraps off of Dan Brown’s table. Numerous conspiracies stitched together from the parts of old theories conjure up secret meetings of Jesuits, Illuminati, and the dreaded liberal lurking in the “cemetery” (a colloquialism for seminary). Others discover new timelines. By revealing “forgotten” prophecies like the 2520, haunted theologians hope to reset the time that is out of joint, like a physician would reset a bone. But we don’t stop there.

We are warned about spiritual formation, historical-critical method, and anything from a non-Adventist. We have a necromantic relationship with spiritualism. We search for it everywhere, even discovering a “Type 2 Spiritualism” link to women’s ordination. In her 1901 sermon Ellen says, “Oh, I see a lot of buzzards, and I see a lot of vultures that are watching and waiting for dead bodies, and we don’t want anything of that. We want no picking of flaws in others” (Ms 43c, 1901); but we see wraiths among our own people; whether it is the fear of a perfectionistic last generation theology at GYC, or suspicions of spiritual formation from the One Project. Ellen White asks, “Is there any of the glory of Christ in suspicion and evil surmising, in criticism and condemnation of our brethren?” (Review & Herald, July 2, 1889). Adventism acts scared of its own shadows, and a casts shade on its own members.

The result of our dark warnings, of making Jesus the center instead of the front and center of our message, means people think more of what’s wrong instead of what is right, even on their deathbed. I have found even the most devout dying Adventist frightened that they may have done something to lose eternity with Jesus. It’s hard to have the assurance of salvation when there’s always a “creeping compromise” around the corner.

I wonder if our fascination with darkness is self-medication. We have grown weary waiting for Jesus and so if we can at least catch a glimpse of the Devil working according to our prophetic framework then there might be hope. Instead of being content working for Jesus, we watch the devil work and develop a hunger for heresy. This dynamic, combined with a resurgent belief that only a perfect people that will vindicate God, allowing Him to return, lead us to our most monstrous tendency.

The Purge

In Post-Traumatic Public Theology, one essayist observes that in cases of terrorism “disfigurement is used to permanently register the pain of one’s own indignity in the flesh of another” (Betcher). In Genesis 4, when Cain’s sacrifice fails, God attempts a teachable moment. Instead Cain internalizes his failure as shame and kills his brother. Shortly after, Cain is confronted by God, who notes the felt absence of his brother Abel. “The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground” (Gen. 4:10). Cain’s shame only fuels his hatred more as he venomously claps back “Am I my brother’s keeper?” In moments of shame and personal failure we are more comfortable being executioner than keeper.

Those preparing for the Annual Council have discussed how to respond to what is perceived as an unjust violation of authority. One way is to add insult to injury—to add humiliation to the recognition of certain delegates who are not in “compliance.” To mark the wound felt by the General Conference in the names of others in order to disfigure their credibility. Another response could happen through a literal cutting off of ties with parts of the body—phantom limbs that will cause phantom pains. We could also remove certain leaders, or their names from our Yearbooks. We could even move people to Australia, but history shows those absences will be felt and those we unjustly banish have a way of coming back.

I must pause to comfort the whataboutists who might be spooked by the possible implication that accountability, repentance, and the healing of trauma don’t matter. This is not my point. The point is when we feel shame and guilt, it can result in violence towards our brothers and sisters. We create “false weights and measures” that will only conjure up more angry spirits, that will follow us to more Annual Councils.

Haunted House

Jesus once called the representatives of religious establishment tombstones (Matthew 23:27)—a ghostly metaphor. Myers (2017) has labeled the church in the West “a haunted house” (Preaching Must Die, 2017)—and based on our unique history, Adventism may be the most haunted of all. There are many ghosts in the church I could speak of, but time is short and my intent is more create awareness of how we have dealt with our shame and fear in the hopes of doing something better at Annual Council. Brené Brown observes that “we have to respond to shame in a way that doesn’t exacerbate shame” (Gift of Imperfection). Brown notes that “shame is the birthplace of perfectionism” which removes “self-compassion”—and also removes compassion towards others.

1 John 4:8 says, “There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear.” We must learn to mourn in a way that leads us to invite the Holy Ghost to haunt our hearts, that transforms our shame into a vulnerability that rests in God’s love for us and leads to a generous trust in each other’s ability to hear from God. Jesus once told a story that sought to temper his disciples’ zeal to purge as a means of perfecting the Kingdom (Matthew 13:24-30). Perhaps we need to learn to be content to let the perceived tares grow among the wheat, instead of tearing them up and reducing the garden plot to a burial plot.

May we remember the words of Jesus and avoid another Tale of Tarers.

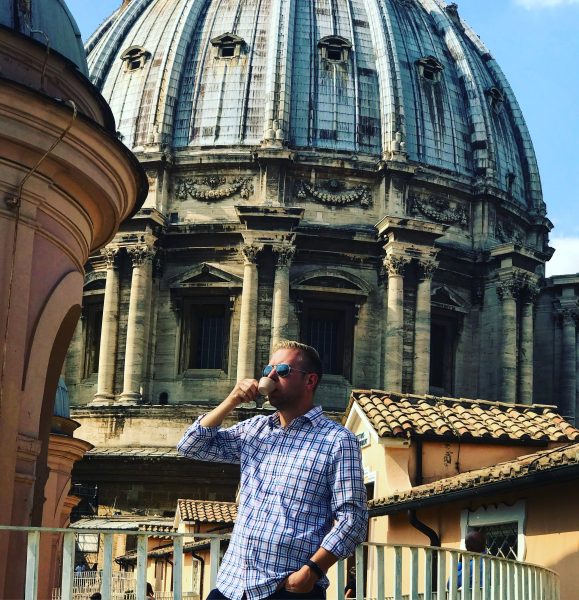

Seth Pierce is a published author and pastors in WA Conference. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Communication. Seth enjoys spending time with family and friends, doing mountains of homework, and occasionally drinking an espresso on top of the Vatican to freak out Adventist sensationalists.

Seth Pierce is a published author and pastors in WA Conference. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Communication. Seth enjoys spending time with family and friends, doing mountains of homework, and occasionally drinking an espresso on top of the Vatican to freak out Adventist sensationalists.