Pivoting Toward Our Conspiratorial Side

By Loren Seibold | 15 January 2021 |

White Adventism (apart from a few institutional congregations) isn’t what it used to be. When I grew up every little town, even in the relatively empty plains states where there wasn’t a patch of dark human skin to be discovered, had its own Adventist church, and those few regions that didn’t were marked (with unintentional irony) as “dark counties.” Now, most of those counties are dark, and the remaining churches in the small cities and villages are shedding less light than the dying glow of a smoking candle wick.

What to do? Our evangelistic methods aren’t working as they once did. We need to find a new way to reach the United States of America, a new audience that is excited about what we have to offer.

And I think, last week, we may have found it.

Angry white people

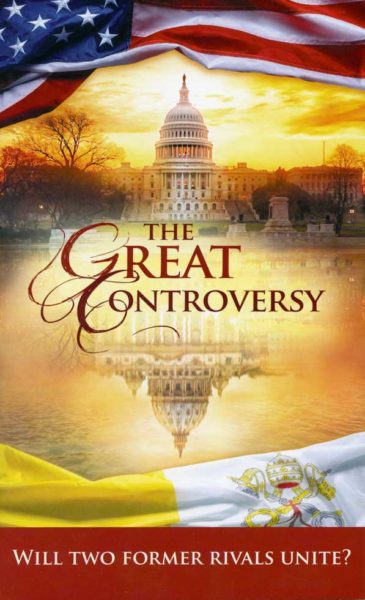

This idea came to me when Adventist Today published a news story about how an independent Adventist group, Forerunner Ministries, had handed out thousands of copies of The Great Controversy to the mostly white crowd gathered at the United States capitol building. The organizer, Christopher Hudson, reported that the folks his team talked to were enchanted by his description of the message of the book as our government’s betrayal of the constitution.

Seventh-day Adventism is intellectually a broad group. By which I don’t mean that we officially sanction a broad set of beliefs—we don’t—but that we contain people of many different levels of intellectual understanding. On one hand are those (among whose number am I) who were blessed by our strong Adventist school system, and grew up to be educated professionals. This cohort has been both beneficial and maleficial to the church, because while they have expertise and money, they also ask troublesome questions.

Church leaders don’t like troublesome questions. It’s why some of our colleges conflict with the church hierarchy—why, for example, Ted Wilson dislikes La Sierra for its professors’ liberal stance on origins.

Ironically, people like me, a person with a doctorate (albeit the kind Tucker Carlson would refuse to acknowledge) aren’t the people who are attracted to our evangelistic advertising. My experience doing public evangelism is that our advertising pulls in a certain type of person: those who like things that are mysterious, tribal and conspiratorial, that appeal to the intellect superficially in the service of deeper unexamined primal fears.

Rarely do we baptize physicians and attorneys and college professors—those, we grow internally, and then tell them they’re not real Seventh-day Adventists because they ask too many questions. Our advertising attracts people who want to know about 666 and the Antichrist and the mark of the beast and persecution and world governments and spooky prophecies about “blood on the moon”—and who will accept most of our assertions with few questions.

So when Christopher Hudson announced he was distributing The Great Controversy to a crowd of pseudo-patriots who believed, contrary to all factual evidence, a conspiracy that the election was stolen from their candidate, I doffed my hat to him (remotely, of course). I suspected that he had just discovered an ideal audience for what we’ve been talking about. A conspiracy for conspirators!

Even the version of the book they handed out was perfect for the event: a picture of the United States Capitol against a violently yellow sunset.

Confluence of interests

The lesson from Forerunner’s warm reception on Sedition Wednesday is that we may not have gone quite far enough to reach a crowd attuned to our message. We have a wonderful new opportunity for evangelism if we push beyond our controlled, civilized, anticipatory fear, to some actual, on-the-ground action.

We have had all along, it turns out, the ideal tool for the job: a conspiracy story given to us by God through prophecy. Take that to an angry mob who are open to conspiracies of many kinds, and you may find a not perfect, but perhaps workable, confluence of ideas.

Consider these points of agreement:

The United States government can’t be trusted. We said that long before the capitol rioters thought of it. So untrustworthy is our government that we say they’re going to persecute us. Some of the capitol mob think the government is so untrustworthy that our elected leaders should be persecuted.

It’s about God and Jesus and stuff. Many of the protesters, and some of the groups that fed the mob, said they were Jesus-followers, more or less—assuming a Jesus who would carry assault weapons and ziptie handcuffs, call for his opponents to be hanged, break doors and windows, poop on the floor, and be motivated by violent racism.

But they carried crosses and Bibles, so there’s that.

We want it all to come to an end. Like us, these groups have a strong apocalyptic strain, at least to the extent that they want to tear it all down and start over.

We both have people we fear. We Adventists fear Roman Catholics—we can’t quit talking about them. The radical right-wingers distrust Jews, people of any color of skin darker than white, and immigrants from everywhere except maybe Denmark, Sweden and Norway.

We all fear the government overreaching on people’s liberties. Countering threats to religious liberty and expression has been perhaps the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s best work. The capitol mob’s fears are different, but at least we share a broad general concern for freedom to do what you want to do.

Adjustments

At first look, these protesters don’t seem a lot like us. We’ve said that God is going to tear it all down and start over, not angry mobs of white people. As for civil liberties, they want to carry guns and overturn elections, while we just want to go to church on Saturday. (In this, they have the stronger argument: no one has tried to take away our Sabbath, but many want to take away their guns.)

One big difference is that we are over-organized, while they operate in a state of poorly informed anarchy. Here’s where we can be of assistance: we have a belief structure upon which they can hang their fears.

It’s going to be a stretch. Still, I know from Adventist Today’s comments and letters to the editor that there are Adventists who already have one foot in this territory. I suspect there are congregations that could make angry nationalists feel at home.

It’s true, we’re going to have to make some adjustments. We will all have to become Republicans or Libertarians. (Which means some of us will have to attend Democratic Party meetings secretly—good practice for the Time of Trouble, I suppose.) We’ll have to get used to guns in church. I’m not sure what we’ll do with all of our black members, though I hope they’ll be okay if they become Republicans. Christopher Hudson, who’s black, circulated among them quite comfortably, it appears, probably because the book he gave them sounded sympathetic to their cause.

As I’ve said before, we Adventists don’t have a lot of actual evidence for what we’ve prophesied. But the people we’re targeting don’t require a lot of evidence. They have shown themselves willing to believe cunning fables and unconfirmed predictions as readily as they do proof. A good evangelist ought to be able to connect to them, with a modest adjustment of language and costume.

That means backing off all of that “Jesus loves everyone” (“red and yellow, black and white”) talk in favor of the lingo of the right. No suit and necktie, just jeans and T-shirts with conservative slogans, and a shoulder holster. Our evangelists’ language will have to change: accusatory rather than conciliatory, I think.

We start with what we have in common: conspiracy and fear. We’ll attempt to redirect their anger from abortion to the possibility of Sunday laws. We’ll need to flip them from hating Jews to hating the Vatican, presenting our case for the horrible things we expect—nay, hope—the Vatican is going to do to us.

Ultimately, we’ll want them to think less about the nation and more about our church. I’d also hope we could reign in their violence, though if the Vatican actually comes through with what we’ve said the Vatican wants to do to us, their guns may come in handy.

As I said, a good, well-armed evangelist should be able to bridge the gap.

Our conspiratorial mind

I admit, I question why our pioneers came up with the kind of eschatology that they did. I’m not talking about the blessed hope of Jesus’ return, but the whole fearful story that backed it up. I wonder why our 19th-century pioneers, whose ancestors came from countries with monarchies and state churches to one with democracy and freedom of religion and speech, within a generation began fearing and accusing their adopted country. They made the bison-like beast in Revelation 13 a symbol of a schizophrenic America: it looked like a lamb but roared like a monster. Then they said this beast was going to team up with the Catholic Church to persecute us, so we should live in a state of expectant paranoia.

Think about that. We would scorn anyone who is anti-Semitic, would we not? But we are proudly—officially—anti-Catholic!

I have struggled with the notion that this all came from God. First, because I see nothing in the gospel that requires us to interpret the Bible allegorically and algebraically, in order to end up with a story that demonizes the world’s largest Christian religion and gives our children nightmares. Second, because it originated more with Uriah Smith than the Bible or Ellen White. And third, because it hasn’t come true. You can’t manage a false prediction simply by saying, “Just wait for it… keep on waiting… don’t stop waiting… yes, I know it’s been 200 years, but just wait—it’s going to happen… soon.”

We’ve done an astonishingly good job at keeping this conspiracy alive, even after two centuries. We’ve had plenty of time to say, “We appear to have been wrong about some of this. Perhaps we should begin to emphasize some of the other wonderful truths that God gave us, and sideline our fearful expectations.”

But no. In our evangelistic meetings, we’ve made apocalyptic conspiracy our selling point. Which leads me to the conclusion that these teachings are about us, about our mental and emotional state—and not at all about the gospel of Jesus Christ.

That is to say, we appear to be, at heart, a people who revel in a good conspiracy.

All I am suggesting is that if, after almost two centuries of disconfirmed expectancy, we have not been able to move ourselves out of our conspiratorial mindset, that we should now pivot directly into it. Let’s admit that this is who we are. Let us move from educated rational Adventism, to an Adventism of radical myths—which we are equipped by history and message to embrace.

Let us step boldly into this moment and make evangelistic use of the alignment between our conspiracies and those of the radical right, between our fear and their anger. We’re not exactly the same, but we overlap some of the same ideological (using that word loosely) territory. Play our cards right and we could become the church of the look-for-it-all-to-come-tumbling-down crowd.

We might, at long last, replace the Mormons as the most interesting of the American sects.

Loren Seibold is the Executive Editor of Adventist Today.