On Motives

By S M Chen, posted Sept 16, 2017 “A man generally has two reasons for doing a thing. One that sounds good, and a real one.” –J. P. Morgan (1837-1913), American financier and banker

I was a youngster of perhaps six when I first became aware of the word “motive.”

Late one afternoon, when the sun hung low in the sky like an overripe orange bending the twig from which it hung and about to drop, I trudged across the expanse of field that lay to the north and separated our house from that of my piano teacher.

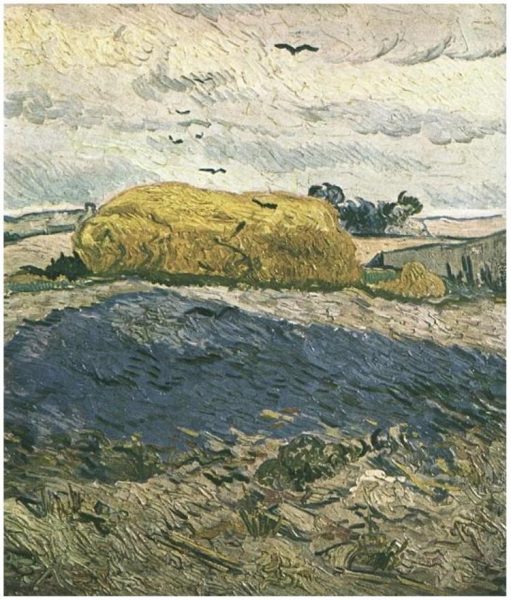

Bales of hay lay about like those that, years before, had inspired artist Vincent Van Gogh (he of the abused ear). Awaiting pickup by farmers for livestock, they lay about like so many gigantic loaves of bread in a vast outdoor bakery.

I could breathe deeply and inhale the aroma of newly mown hay. It would be a number of years before I developed hay fever.It was with some dread that I directed my feet northwest, for I knew that upon my return, after the piano lesson, the sun would have disappeared and the moon would not yet have made its appearance. It would be nearly pitch black and, like a blind man groping about, I would slowly make my way home, more shuffling than walking. I did not have a flashlight. My parents had not given me one and I had not thought to ask.

In the home of the piano teacher, an angular woman with aquiline features who later came to mind when I saw British actress Maggie Smith in various film roles, I sat in a chair awaiting my lesson. I would have preferred that my feet reach the floor.

Teacher was in dialogue with her adult daughter, a younger, less angular version of herself, who played violin as well as the Steinway.

“What really matters are motives,” teacher intoned. “That is what we will be judged by. If motives are right, everything else will follow.” She seemed quite certain.

“Motives” was a new word. I could only guess as to its meaning.

“How does this tie in with morals?” asked daughter, her features softer than her mother’s. I had heard of “morals.”

“Not directly, I should say.” The accent was difficult to place but not unpleasant. I would later learn it was South African. She and her husband had been missionaries before they moved to town. “What I am saying is that right motives are the important thing. Regardless how something turns out. I daresay if motives are right, usually the end result is salutary.”

“Are you allowing for exceptions to the rule?”

“Ah, exceptions… I rather dislike them, though they are inevitable, aren’t they?” She stroked her chin, then smiled.

Teacher turned to the girl with blond curls who had been sitting quietly at the piano. “Sorry, child. I didn’t mean to interrupt your lesson. Carry on… Where were we, now?”

“We were on page five. But…” Curls looked at me. “I think maybe my lesson is about over.”

Teacher glanced at the ornate clock on the wall. There was nothing bourgeois about her taste. “You’re quite right. The young lad has been waiting patiently while I’ve been jabbering on. Off you go, my dear. See you next week. And don’t forget to practice your arpeggios.”

***

As with some other things, it seems motives and actions lend themselves to rendition in matrix format, with “motives” and “actions” on an abscissa and “good” and “bad” on an ordinate. Or vice-versa.

Motives can be either good or bad. As can actions.

***

Bad motives, good actions.

Some Jewish leaders in early C. E. had good actions, which drew Christ’s commendation. But often they sprang from bad motives (pride, the desire to be seen and praised, even if it were puffery), which negated their virtue. Jesus called them whited sepulchres, containing the bones of dead men.

Such mentality was not unique to that time. Not long thereafter, Ananias and Sapphira did a good thing with their largesse. But, when, in response to a query about their gift, they lied, justice was swift. Their mendacity did not go unpunished.

I sometimes wonder if they would have escaped punishment had they remained silent, rather than answer. They may not have been well acquainted with silence.

When the rod of Moses struck the rock in the wilderness (ostensibly a good thing; it did bring forth the sought after water), it sprang from a motive of Mosaic frustration, which led to disobedience.

One might argue this was a small thing. But the Almighty is a God of small things (and also not so small). That one action kept Moses from entering the Promised Land. His ultimate outcome, however, is one over which the Evil One may still chafe.

***

Bad motives, bad actions.

Perhaps the earliest recorded example is that of Lucifer. His pride and ambition led to his rebellion and downfall. Instead of ascending, which he envisioned, he and his cadre descended. It has been downhill ever since.

Then there was Eve in Eden. Distrust of God (and trust in the serpent/devil) led to partaking of forbidden fruit. Forbidden fruit is sometimes thought to be sweet, but the aftertaste is almost always bitter. When, later, Adam and Eve cradled the dead body of Abel, it is difficult to imagine their tears being anything but bitter.

By choosing the secular over the sacred, the profane over the sublime, the dark over the light, man has aligned himself with the forces of darkness. And it would remain so were it not for divine intervention, which, to paraphrase the book title of contemporary author Milan Kundera, provided a Being of almost unbearable lightness.

***

Good motives, bad actions.

It would seem that, in the parable of the two sons in Matthew 21, the one who said he would go, but did not, fell in this category.

The road to hell may indeed be paved with good intentions.

During WWII, some people of compassion sheltered Jews, at the risk of their own lives. If, confronted by occupying Germans, the desire to be truthful (good motive) overrode that to save a fellow human being, the shelterer might reveal the whereabouts of the Jew (bad action). Or not.

Does the end justify the means?

Such an ethical dilemma faced Rahab, who sheltered two Hebrew spies in Jericho.

After the spies departed, she lied about their whereabouts (good motive, bad action; or, depending on one’s perspective, perhaps the opposite: bad motive = the desire for self-preservation – and good action = saving the lives of the spies).

Yet, by virtue of a single scarlet cord, she and her family were saved when Jericho fell. They may yet be saved again at a future date.

In Les Miserables, masterwork of Victor Hugo, protagonist Jean Valjean steals a loaf of bread for the starving family of his sister. For this act he is imprisoned 19 years.

Things may not always be black and white. The Almighty may also be a God of shades of grey.

***

Good motives, good actions.

The most optimal of four possibilities is that of good motive leading to good action.

Some of the people we most admire are those whose good actions sprang from perceived good motives.

Siddhartha/Buddha, St. Francis, Mother Teresa. Oskar Schindler.

And, of course, Christ.

The list is notable for its brevity, but there may be many unsung heroes who have floated down the rivers of time, about whom we may only someday learn more.

***

So was my piano teacher right?

She may not have been entirely right, but I do think she was more right than not.

Why else would, decades later, that little incident adhere to memory?

S M Chen lives and writes in California.

S M Chen lives and writes in California.