How Missionaries Shaped African Adventism

by Arthur Sibanda | 27 December 2019 |

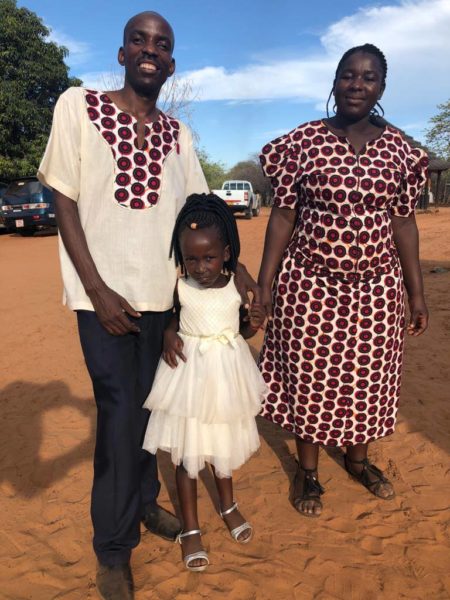

“Daddy, uJesu likhiwa yini?” (“Daddy, is Jesus a white man?”)

The question caught me off-guard. My daughter is only five, and yet I found myself struggling to mumble a response to her innocent question. Because her question reflects the collective fears and insecurities of Christianity in Africa. Christianity, and Seventh-day Adventism in particular, seems to need continuously to authenticate its genuineness in the wake of the colonial influence.

With the current rise of African consciousness and pan-Africanism, and open access to various philosophical worldviews, the church cannot afford to continue ignoring the rising challenges to its legitimacy in Africa. Pan-Africanism views Christianity as a Trojan horse that facilitates a western agenda. Younger Africans, unlike their forefathers who would gobble down everything the mnali (missionary) would say as a direct instruction from God, have the courage to ask questions about whether Christianity is a relevant and necessary element of the African experience.

How much of modern-day Adventism in Africa is a direct influence of the views and cultures of the early Western missionaries who first settled in Chief Soluswe’s lands in 1894?

The Childhood Pictures

I grew up in a typical Adventist home. My mother, who was a literature evangelist, would read to us from Uncle Arthur’s Bedtime Stories and The Bible Story books. My first name came from Arthur S. Maxwell, and I still think it’s a cool name to bear.

These books were character-building stories for children. However, my early childhood recollections mirror my daughter’s question. My first impression of heaven was of a place with a lot of beautiful white people, but few black people. The colorful pictures mostly showed white children around Jesus, white Bible characters, and scenes from western backgrounds. When I was still of tender age, I wished I was white too, just like the children hanging around Jesus in the storybooks.

(Some of the concepts were confusing, because they didn’t apply to us: I remember a story of a girl who lost her “mittens”—something I later learned were similar to what we called “gloves,” but for weather so much colder than we could imagine.)

We did have some culturally relevant storybooks, such as Story Time in Africa. But I didn’t like the pictures in those volumes: they were not colorful, and were a little scary when compared to Uncle Arthur’s books.

As I write this, I struggle to make this a balanced discourse, as I am aware that I am treading on eggshells. But it’s important to say, because it could be argued that most of my spiritual views were shaped by those storybooks.

An Adult View

I am grown now, and I have intentionally revalidated the values that my parents taught me when I was young. Yet many of my questions about missionary influence remain.

Currently, Africa is a beehive of Christian activity, with innumerable church denominations, pastors, televangelists, prophets, and the never-ending yearning for the miraculous. The Seventh-day Adventist Church, not to be outdone, is growing exponentially in Africa.

The sad truth, however, is that Africa is still sinking beneath poverty and poor governance. Our apparent religiosity is not improving the quality of people’s lives. Most African countries rely heavily on donors and handouts from bigger world economies. This dependency syndrome is reflected in the church, too. Is it possible that there is a relationship between the quality of the Christian experience in Africa and the abject poverty and catastrophic ills that have been characteristic of this continent?

I have watched many live church services from Adventist congregations in the Western world on the internet. I have read books and articles by different Adventist theologians. I find there is a huge philosophical chasm between the Western church and most local churches in Africa. This is made apparent by comparing the quality of the sermons preached in the West versus the Third World. It could be that our preachers feel the need to contextualize. However, I do not find it amusing that those preaching to people in poverty seem to preach more often of the nearness of Jesus’ return at the top of their voices, as if out of desperation. Africa seems in a great need to have the Second Advent emerge sooner than the First World wishes.

This produces Christians who live in an eschatological escapist bubble: people who are engrossed in the world to come to the extent of being of diminished practical use to the communities they live in right now.

I feel that the Western world church has made strides in developing mature theological thought that is stable and holistic. It has managed to overcome the urge to ruminate and dwell on the Second Advent as the only important truth of our faith. I am not so naive as to think that the West is perfect and has no nagging issues of its own—only that this progress in the West deserves to be appreciated.

I will submit that the stagnation I have observed in some local African congregations reflects in part the heavy influence of the views of the early missionaries.

Eschatological Urgency

Given that missionaries settled at Solusi fifty years after the Great Disappointment, it is possible that their early witness in Zimbabwe was driven by an eschatological impulse. Jesus was still perceived as about to come very soon. Perhaps this urgency led them to direct their native congregants to focus on what I believe were the external aspects of the religious life.

Whatever is said in a hurry tends to be miscommunicated or misconstrued. There was pressure to do the right things, as people quickly got ready for Jesus’ coming. Since Adventism emphasized having the truth in an absolute sense, Adventist culture was taught as something that could not change. We Africans didn’t see the need to further investigate what had been taught us by people whom we considered superior. The idea of truth’s being progressive was not a concept the natives grasped—and I doubt it was ever even suggested to us.

Africa is historically tribal, and consequently respectful of elders, which tends to make us as a culture naturally conservative of the past. We have held on to what we were taught by the missionaries. African Adventism is now in the interesting situation of blaming their Western brethren for compromising the truth the West originally taught us.

Surface Issues vs. the Deeper Truth

Africa learned surface issues instead of deeper truths, and those are what we have held on to. We understood certain things that made us distinctive from other Christian denominations, and those distinctives became central. The missionaries tended to focus on lifestyle codes aimed at producing prim and proper “wise virgins” awaiting the second coming.

Dress

Once at my rural church a young man who was supposed to go up front wasn’t wearing a jacket. The church leaders insisted he borrow a mismatching jacket. It didn’t matter that it wasn’t his size, or made him look like a Christmas tree: it was what he must wear to be “presentable” before God.

We learned from the early missionaries the importance of modest dress. What was modest dress? The missionaries taught the native women to cover their bare breasts, do away with cultural beads, trim their African hair, and exchange their animal skins for fabric.

Yet it went farther than that. Men adopted the European way of dressing—suits and ties—and women went out of their way to chemically straighten and lengthen their hair so that they approximated the appearance of the missionary wives. This manner of dressing has continued to this day. I have met those who have told me that they would not be able to attend an Adventist church service because they don’t have suits.

Some Adventist congregations host an African-themed Sabbath Day (usually on Africa Day) where members are encouraged to wear traditional clothes to church. I find this troublesome only because it suggests I can be my true self and have my culture accepted in my church once a year.

Worship Music

Worship Music

The early missionaries had a difficult time trying to help our forefathers develop a new taste of music, and wean them from the tribal ceremonial war songs and songs used in ancestral worship. Every aspect of indigenous expression had to be weeded out in order to ensure that the new converts would not revert to their former dark ways.

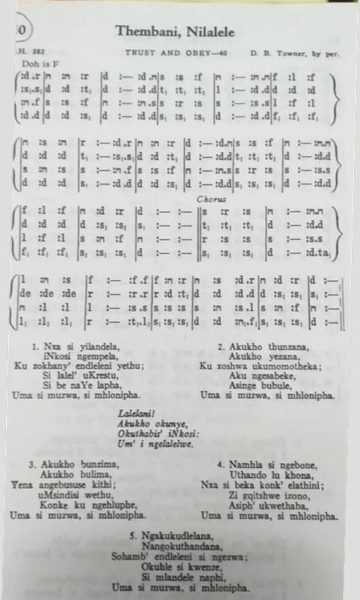

However well-intentioned, the result was that every element of native expression was suppressed and demonized, while every Western cultural expression canonized. In my country, we are encouraged to stick to Adventist music, a term that generally means we should sing only hymns. The Adventist Zulu Hymnal (UKrestu esihlabelelweni, translated as Christ In Song) has been elevated to the level of the Bible and Spirit of Prophecy. I have been in afternoon music ministry programs where we are taught that hymns “have a message” and were written by people “inspired by God.” The hymns have “notes” and hence are structured in a way acceptable for worship. In some congregations culturally relevant songs, such as choruses, are shunned.

Now some churches have Africanized the music, ignoring the notes and letting the song flow with emotional and cultural expression, increasing the tempo and rhythm and adding body movements.

Food

Missionaries felt that the nearness of the advent required quick reform, and one area that the natives needed to master was a vegetarian diet. But parts of sub-Saharan Africa were not good for production of Western crops, so there was a lack of variety of “fruits, grains and nuts.” This posed a theological conundrum for Adventists trying to follow health reform to the letter.

The consumption of meat nowadays does pose a health risk. However, I know people who developed vitamin B12 deficiency and had to start paying for monthly injections to correct the condition. Some were not so lucky: refusing to go back to using animal products, they developed complications and died. I guess this issue was a strong moral standing point: they genuinely felt the deficiency came as an attack from the devil and so they needed to resolutely resist going back to a diet containing animal products.

Women in Ministry

Painting all African societies and cultures as patriarchal is a misrepresentation and overgeneralization of African history and culture. Some African cultures were matriarchal—they had queens as rulers. We can cite Queen Sheba from the Bible as the first example (see 1 Kings 9:27), though there are others mentioned in secular history.

I attribute the male headship view, which is now widely accepted in Africa, to the culture brought by the missionaries. Working in God’s vineyard was seen as a role specially ordained for men, while women were to find fulfillment in domestic duties and supporting the ministry of their husbands. I have no recollections of any early female figures in Africa who ministered the Word.

Though there have been attempts to find scriptural basis for this, I find the modern applications of the teachings of Paul in male-female relationships (see Eph 5:22-24) to be uncomfortably close to what Paul in later passages said of slave-master relationships (Eph 6:5-8). While the former has been used to ignore the giftedness of women to minister in God’s vineyard, the latter was at one time seen as a Divine endorsement favoring apartheid. Just as Paul’s words have been used as an excuse to perpetuate the colonization and enslavement of Africans, with the same logic they are oppressing the full expression of the spiritual gifts of women.

Fear of Change

It is a grave mistake to take what is written without taking the context into consideration. This is a contentious issue for us in Africa, especially when you realize how often we are sticking to what the missionaries taught us, not what reflects God’s heart. (If you think I’m wrong, sit down with me over a cup of rooibos tea without milk and we’ll discuss it!)

I sincerely believe the missionaries were Spirit-led, self-sacrificing individuals whose courage and commitment should be admired and emulated. I do not mean to disparage and minimize the great Adventist foundation they laid. My primary concern is how most local congregations, at least from what I see in Zimbabwe, remain stuck in reminiscing on the good old days of “Stutuveti” (the local name of one of the early notable missionaries in Zimbabwe, Melvin Sturdevant).

My daughter’s innocent question illustrates how views about Jesus taught in church seemed to us to elevate one particular culture at the expense of others. Indeed, accepting Jesus into one’s life is a process of losing one’s identity and sense of personal pride. But in the case of the missionaries, it also led us to lose our own culture and be dominated by a foreign one.

The older generation of African Adventists shudder in fear and suspicion when they see changes in the church. Changes are sometimes viewed through conspiratorial lenses. Any new understanding or method different from what the missionaries taught is seen as a threat to the corpus of true Adventism. There is fear that the younger generation is trying to destroy the great pillars of our faith laid by our forefathers.

Why This Is Important

This fear of change stagnates our experience, and as a result Adventism loses relevance, meaning and fulfillment in the lives of modern Africans.

I am not here advocating for some particular new idea or another. I only ask Adventism in Africa to mend the inner structure supporting the African psyche. I am of the view that a healthier version of Christianity will result in an improvement in the lives and livelihood of the ordinary person in Africa. Christianity, when applied correctly, will provide evidence of its valid necessity in the lives of Africans, and will cease to be seen as a colonial instrument.

Western theological thought has progressed and matured in a lot of ways on the issues I highlighted above. I attribute this to the emergence of individuals who rediscovered the great central truth which ought to be preached to the world, a truth far more essential than the second coming: the revealing of the character of God to the world. As Ellen White wrote, “The last rays of merciful light, the last message of mercy to be given to the world, is a revelation of His character of love” (COL 415).

This cannot be preached in a hurry. The subject of the everlasting Good News when rightly understood will promote church unity and usher in the second coming (see Matthew 24:14). The study of the love of God when placed at the center of Adventist doctrine brings stability and helps us to avoid majoring on minors and bickering on the non-essentials.

Sadly, some Western leaders and the majority of those in Africa seem stuck in the “good old ways,” desiring to hold on to some mythical Golden Age of Adventism. It is comfortable and reassuring to do so, and it gives them a sense of control. However, if we fail to move on to the weightier matters of God’s law (Hebrews 6:1-3, Mathew 23:23), we will never learn the deeper universal principle of God’s love, and the quality of our Christian experience will not improve.

Arthur Sibanda is a mental health nurse in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. He and his wife, Mercy, have one daughter, Nobukhosi Tashanta. He enjoys writing, composing songs, and singing, and is also involved in a ministry helping people overcome sexual brokenness.