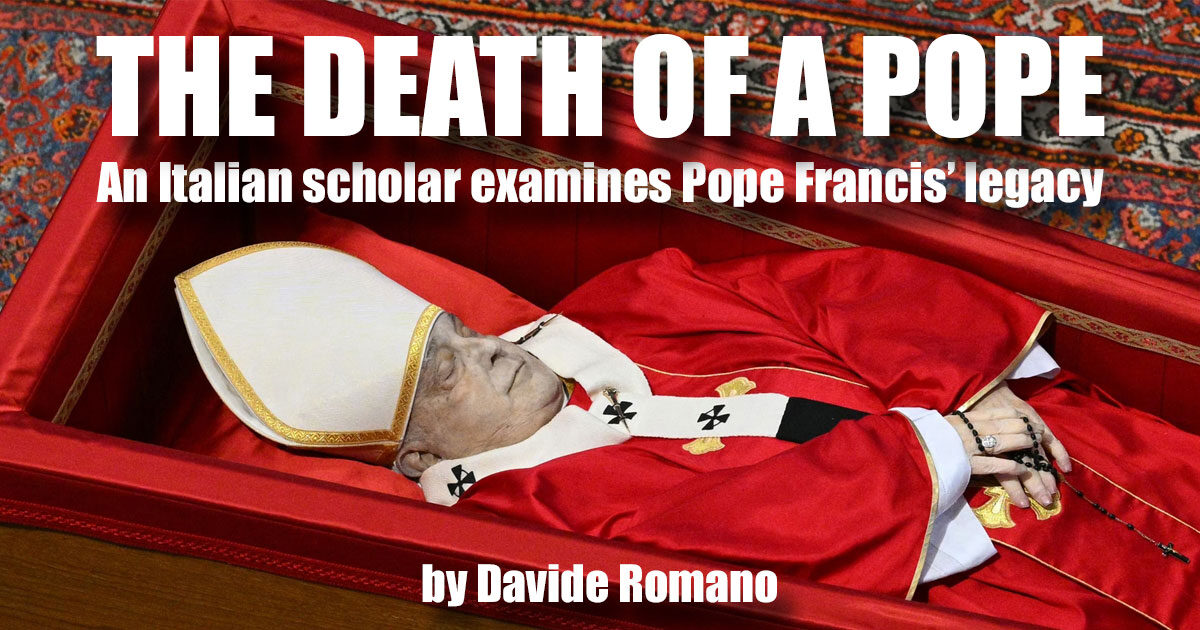

The Death of a Pope

by Davide Romano | 13 May 2025 |

On Monday, April 21, at 7:35 a.m. Pope Francis’s death was announced. The news, as always when a pope dies, shook many people. And, as expected, it immediately set off the formidable media apparatus in Italy and the whole world. This significant event saddened Roman Catholics, and also called forth statements of solidarity from voices in culture, politics, the church, and the entertainment industry.

Many believers identified with Francis’s style and message, and mourned him as a good pope who tried to shake up the Catholic Church and move in an Evangelical direction. To these, Pastor Andrei Cretu, president of the Italian Union of Seventh-day Adventist Christian Churches, issued a message of solidarity and condolences.

As Adventist Christians we believe that death is a sleep from which we will be awakened on the day of the resurrection, as Easter has just recently reminded us. The apostle Paul tells us that “the last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26), and that we will ultimately inherit eternal life with Jesus. Of this eternal life, promised and awaited, longed for—and nowadays, sometimes vilified by skeptics—we can say very little. All our thoughts and even our brightest imaginings are strongly colored by the reality of death and dying. But the resurrection of Jesus constitutes the precedent we must look to as the harbinger of this infinite provision of divine grace.

The legacy of the Bergoglio pontificate

Naturally, a man who is recognized worldwide, who has a role that is by nature not just religious and spiritual but also political, will tempt not just Roman Catholics but also journalists and other Christians to draw up a sort of “balance sheet” of his pontificate.

My point of view is that of an Italian Protestant—a Seventh-day Adventist. My church has not generally been well-disposed towards any pontiff. This is especially true here in Italy, where the word of the pope is often considered by the media as the view of the highest existing religious magisterium: when the pope speaks, they leave it to be understood that his voice represents Christianity.

Considering the copious flood of recognitions and panegyrics that inundate news and opinion websites, perhaps it is useful—if only for ourselves—to hear a more nuanced viewpoint.

A long period of sedimentation is always necessary to evaluate the legacy a pontificate leaves to its church and to the religious and social culture of its day. On the level of impressions, one can certainly recognize in the pontificate of Jorge Mario Bergoglio an affable, cordial style, characterized by a spontaneous inclination to dialogue, including with other faiths and other churches—at least for the first part of his pontificate.

His pontificate was skillfully punctuated by highly evocative symbolic gestures. Among these were the visits to the Waldensian Temple in Turin on June 22, 2015, and to the Anglican Church in Rome on February 26, 2017. The almost clandestine meeting with the Orthodox Patriarch of Moscow, Kirill, in 2016 in Cuba, was also highly symbolic, though on a very different level.

It is hard to be certain whether these gestures, and many others, produced any new ecumenical or inter-religious sensitivity in the Church of Rome. A church with such a long history cannot be suddenly transformed by a single pontificate, whether enlightened or not. In recent years, though, a change was observable: a greater awareness of the spiritual and historical significance of Christian plurality. This was in decided contrast with the previous pontificate of Benedict XVI, but in some ways in continuity with the more auroral spirit manifested during Vatican II.

Bergoglio’s passion for a plurality of voices and sensibilities, including within Catholicism, found visible confirmation in a more convincingly synodal imprint that the Church of Rome sought to rediscover under his guidance. It can certainly be recognized that neither of the two previous pontificates had insisted as much on synodality.

Yet in Pope Francis’ conduct there was no lack of internal reprimands towards forms of Catholicism not to his liking. This affirmed once again—fatally, perhaps—the form of a church whose episcopate robustly limits and humbles every real synodal aspiration.

Most of Pope Francis’ theological writing has dealt with important current themes, such as conjugal love (Amoris Laetitia, 2016), friendship (Fratelli Tutti, 2020), and the right ethical attitude towards creation (Laudato Si’). His little-cited Lumen Fidei (The Light of Faith, 2013) is, in my opinion, among his clearest and most consequential works of Christian dogmatics.

A revolutionary Pope?

Many adjectives have been used to describe Pope Francis’ pontificate, with the media celebrating every gesture as “historic” even when it was not. The true “innovative” scope of Bergoglio’s reign will vary according to the expectations of the individual.

That being said, it appears that those who nourished a hope for great reforms in the Catholic Church now see the glass half empty, at least in terms of implementation of changes. On two issues which have become classic examples in the debate on Catholicism, Pope Francis’s actions seemed unrealistic and weak. The first is women’s access to the ordained ministry, if only as deacons. The second is getting beyond clerical celibacy, at least for viri probati (married men of proven character), especially after the 2019 famous Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region had raised hopes. On more than one occasion Francis reiterated a strong “No” to the women’s appeals, by affirming the conclusions reached by John Paul II.

Nonetheless some, such as feminist theologian Marinella Perroni, note the importance of the change of register adopted by Francis, who seemed to want to demasculinize the church by placing females in top administrative positions traditionally held by males. In the long run it may well be that these actions will prove to be productive.

It is, however, legitimate to have doubts about the concrete impact that such decisions can bring about in a church body that, from a theological and pastoral viewpoint, has historically thought of itself as exclusively male. Can small and modest changes in the Church of Rome’s organizational chart produce a significant change in mentality? This question applies not only to Roman Catholicism but also the other churches which, to varying degrees, resist the adoption of equal and inclusive gender policies.

The pope’s foreign policy

Without delving too deeply into Vatican diplomacy, we must ask whether Pope Francis’ pontificate has defended the freedom of faith of believers, which in the Catholic sphere means the Libertas ecclesiae—that is, the freedom of the church to accomplish its spiritual mission without interference from any secular power. Has he also promoted values of peace and harmony among peoples “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam”—that is, “For the greater glory of God”—as the motto of his order states?

As early as 2018 the Vatican’s secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, reached an agreement with China regarding the recognition of episcopal appointments, which also allowed the bishops freedom of movement in the exercise of their leadership. This agreement was renewed several times, most recently in 2024. Despite criticisms that have been made about this agreement, it must be acknowledged that it has allowed Chinese Catholics a limited freedom of worship. (The Catholics in question are part of the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association.)

Serious doubts arise, however, as to other strategic choices made by this pontificate.

In consistency with a populist strain of Latin American Jesuit thought, Pope Francis gave voice to some harsh criticisms against the values and priorities of the democratic-liberal West: capitalism, individualism, liberalism, consumerism, the logic of profit, and private property. Yet Francis seemed at times to have had a more benevolent attitude toward regimes that expressed a socialist-populist philosophy. The impression that sometimes emerged was of more sympathy – albeit somewhat hidden – for autocrats such as Putin (at least until 2022) and Maduro than for the leaders of old Europe and the United States.

In this sense the difference from the Polish pope Karol Wojtyla (John Paul II) could not have been more pronounced. Factors of different cultures and historical conditions between Bergoglio and Wojtyla were at play.

His call for peace in a world going through a “third world war fought piecemeal” is praiseworthy, provided that it does not translate, to quote Emmanuel Munier, into a pacifism that through cowardice and shortsightedness serves the enterprises of violence. Bergoglio once suggested during an interview with Swiss Radio and Television (RSI) that Ukraine should have the courage to raise the white flag and negotiate. In doing so he risked legitimizing the victory of the mighty, while demeaning principles of international justice—and gave a big shove to St. Augustine, the father of Just War Theory.

The next pontificate?

It is not for us to express preferences for the next pontificate. The Bishop of Rome, the newly installed Pope Leo XIV, was elected by the Church of Rome gathered in conclave. Yet there are clear risks linked to the selection of a new pope because of the influence that the largest Christian church—which is also constituted as a state—is capable of creating for other churches and other nations.

The concomitant surprise of an American nation currently redefining its own prerogatives and hegemony raises not a few fears regarding a possible pontificate too compliant to the appeals of an identity-based, self-referential Catholicism, one with sympathies towards new political messianisms. Thus I want to say respectfully that a leaning towards a “North American” pope would not necessarily be a good thing.

Davide Romano is the director of the Public Affairs and Religious Liberty Department for the Italian Union of Seventh-day Adventists.

Davide Romano is the director of the Public Affairs and Religious Liberty Department for the Italian Union of Seventh-day Adventists.

To comment, click/tap here.