Should We Fear Vaccines? Joseph Meister, Louis Pasteur & Hydrophobia

by Jack Hoehn

Hydrophobia is a Greek word that you might be able to translate: hydro is water, and phobia is fear—fear of water.”

We fear drowning if we cannot swim, or maybe even getting our Sabbath-best drenched by an unplanned downpour on the walk to church. But why would a mother be in a panic over her nine-year-old son developing a dread of something as harmless, helpful, and necessary as water?

In 1885 Ellen White was in Basel, Switzerland, a Swiss town sharing borders with both Germany and France. White’s team of helpers was translating Steps to Christ, some of her Testimonies to the Church, and the just-published Spirit of Prophecy, vol. 4 (her first exposition of the great controversy theme) into German and French.

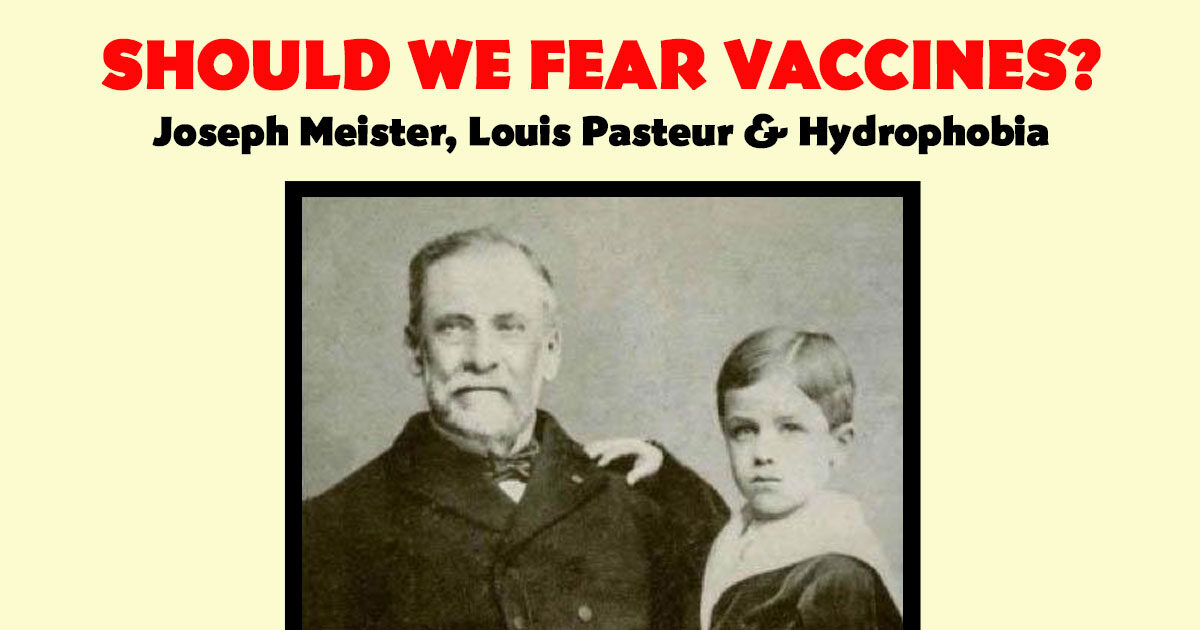

At the time, French newspapers, and soon German and English papers, too, were headlining the story of Joseph Meister and a French scientist named Louis Pasteur.

Hydrophobia

In June of 1885 Joseph was bitten by a mad dog in his Alsace village of Meissengot (now Maisonsgoutte) about 60 miles north of Basel, where Ellen White was then living. His mother was frantic. She had heard about a French chemist named Louis Pasteur who was working on a new treatment, called vaccination, used against rabies in animals. Unwilling to see her child taken in a terrible death, she begged Pasteur to apply his animal vaccine to Joseph.

Hydrophobia was the name then given to the “mad-dog disease,” a transmittable viral disease that we now call rabies. A dog (or skunk, bat, raccoon, fox or other mammal) infected with this neurological virus becomes aggressive with restlessness, excessive drooling (“foaming at the mouth”), difficulty swallowing, and has seizures when trying to drink water. Wild animals lose their fear of humans, while domestic animals such as pet dogs or cats display sudden aggression.

Before vaccines were available, rabid dogs would roam the streets of villages or cities and, without provocation, bite people like little Joseph Meister. A human exposed to infected saliva—usually it was a rabid dog bite—will come down with symptoms in days or months, depending on where the bite was. (It takes longer if on the feet or legs, more quickly on the face.) But once the virus travels the nerves and gets to the brain, symptoms appear, and a terrible death is inevitable in 4 to 10 days. Joseph was going to have difficulty swallowing. He would eventually panic when presented with liquids and be unable to quench his thirst. Saliva production would be greatly increased, and attempts to drink would lead to excruciatingly painful spasms of the muscles in the throat and larynx.

Even today, with best quality ICU care, unvaccinated people with rabies almost all die.

Pasteur was not a physician, but he consulted with two medical doctors, and they agreed that since Joseph was undoubtedly going to die, it was ethical to experiment. Pasteur gave him 13 painful abdominal injections of spinal fluid from rabies-infected rabbits, a treatment that he had already used successfully to prevent transmission of rabies in dogs.

The rest is history. Joseph did not get rabies, in spite of severe rabid dog bites, and lived till the 1940s when he died in Paris during World War II. Vaccination of dogs to prevent rabies, and vaccination of humans bitten by unvaccinated dogs, reduced annual deaths in the United States from thousands a year in 1885 to one hundred a year in the 20th century. Now that universal vaccination of dogs, and prophylactic vaccination of people bitten or exposed to possibly-rabid animals (such as veterinarians) is now widely available, the death rate is down to one or two human deaths a year in the United States.

How disease spreads

In the 1980s, my wife, Deanne, as a missionary in Zambia, was attacked by a rabid dog, but saved from severe bites by her cat attacking and diverting the dog. Since Deanne’s skin was broken by backing into a rose bush to get away from the dog, she and I and our children were prophylactically vaccinated against rabies. (She also had to put down her severely damaged hero cat who’d gotten the dog’s saliva on it.) At that time Zambia only had the old 13-day dose vaccine given into the skin of the belly. I could not bear to do this to my own little son, so I arranged for importation of the newer three-dose vaccine to be flown in for us.[1]

Pasteur went on to prove that infectious illnesses were not caused by “bad air” but by germs and viruses. He proved that milk, cheese, and wine could be treated to prevent infection or spoilage from germs by Pasteur-ization. Since then, the Pasteur Institute has progressed from vaccines against rabies and anthrax to helping control deaths, through vaccines, from diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, yellow fever, and plague.

And what about Ellen White, who was very close to this 1885 story? She did not comment on rabies vaccination at the time, and modern vaccines were not available until the mid-20th century, long after her death. But a primitive form of smallpox vaccine had been available. In 1776, English physician Edward Jenner had observed that milkmaids didn’t get smallpox if they got cowpox (a less virulent disease) from milking cows. Since one in three children who got smallpox died, Ellen White had her own sons with vaccinated.

Unfortunately that vaccine would give the child the related (but less fatal) cowpox. Vaccinated children could be quite sick from cowpox, so although her children didn’t die from smallpox, Ellen White was not at first enthusiastic about the vaccine, and having to watch her boys suffer with it. However, Ellen White’s longtime office assistant D.E. Robinson recorded this history:

“At the time when there was an epidemic of smallpox in the vicinity, she herself was vaccinated and urged her helpers, those connected with her, to be vaccinated. In taking this step, Sister White recognized the fact that it has been proven that vaccination either renders one immune from smallpox or greatly lightens its effects if one does come down with it. She also recognized the danger of their exposing others if they failed to take this precaution.”[2]

Tomorrow: Weighing the Benefits and Risks

[1] This story is documented in Deanne’s book, Loving You—I Went to Africa. Available from Amazon.com

[2] D. E. Robinson to Clarence Hocker, June 12, 1931, Ellen G. White Estate.

Jack Hoehn is known to his patients as Dr. John B. Hoehn, MD (Loma Linda University). His family practice residency was at the University of Calgary Foothills Hospital (with additional surgical training by Dr. Peter Cruse, professor and later head of surgery at University of Calgary). He is a boarded Certificant of the Canadian College of Family Physicians (CCFP), and has a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene from the Royal College of Surgeons (DTM&H-London). He was a physician and surgeon missionary doctor in Lesotho and Zambia for 13 years. He practiced in Walla Walla, Washington, as a family physician until retirement. He is a Life Member of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Jack’s book Adventist Tomorrow is a bestseller for Adventist Today, available in print or Kindle at Amazon.com.

Jack Hoehn is known to his patients as Dr. John B. Hoehn, MD (Loma Linda University). His family practice residency was at the University of Calgary Foothills Hospital (with additional surgical training by Dr. Peter Cruse, professor and later head of surgery at University of Calgary). He is a boarded Certificant of the Canadian College of Family Physicians (CCFP), and has a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene from the Royal College of Surgeons (DTM&H-London). He was a physician and surgeon missionary doctor in Lesotho and Zambia for 13 years. He practiced in Walla Walla, Washington, as a family physician until retirement. He is a Life Member of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Jack’s book Adventist Tomorrow is a bestseller for Adventist Today, available in print or Kindle at Amazon.com.

To comment, click/tap here.